> BACK

revised on

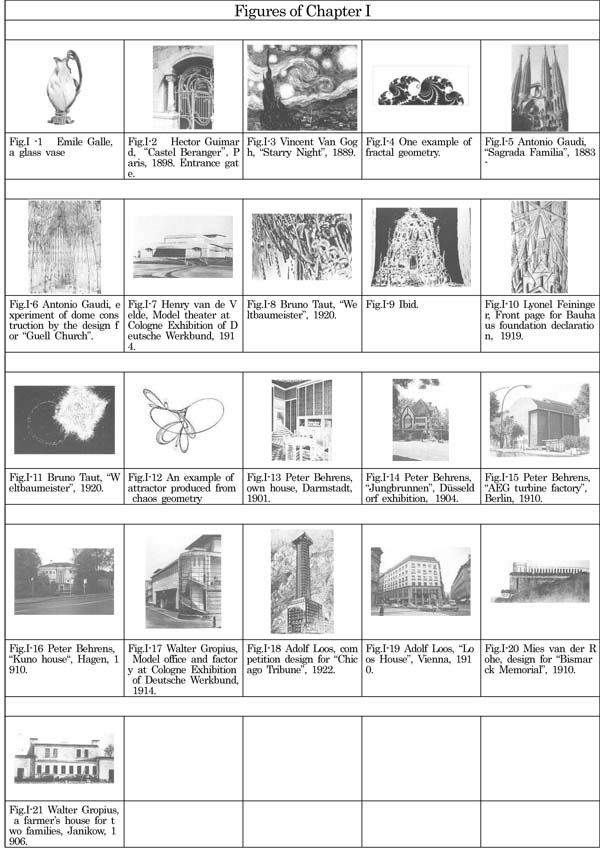

2010.10.16

1. Crucible of chaos

(1) Melting

phenomenon in Art Nouveau architecture

What kinds of things are the phenomena of

fin de siècle, that is the end of a century?

The phrase end of a century has an immoral image, one that matches the

name degenerate art. It is as if, at the end, all order is destroyed and

power is taken by all kinds of evil.

However, why is it that the end must be evil?

Isn’t there something wrong with this preconception? Is there some

reason that the end does not suit a joyous paradise? In Christianity,

the path to either Heaven or Hell is decided at the final judgment. Even

in Buddhism, there is Nirvana and Hell. This is the meaning from the

viewpoint of religion, and we cannot say that the end is necessarily

always evil for people of modern times.

Unlike the ages that emphasized moral and ethical judgments of

right and wrong, in the ages of modern times scientific analysis has

always been placed ahead of judgments of right and wrong. So what is the

end of the century? Is the end of the century something that can be

studied scientifically? Are there any kinds of mechanisms that give rise

to some kind of end of century phenomena? Speaking tentatively, the end

of the century is something that cannot be explained by simple schemas,

and is a time that is wrapped in complex circumstances.

If we take the 1890s at the end of the 19th

century as an example, styles that were very logically indivisible

appeared in the world of design during this period. In

Art Nouveau means “new art” and Secession means “separatism.”

Both of these featured a departure from previously established concepts

of value, and were not originally envisioned to become mainstream. On

the other hand, academic styles originated from the different

standpoints of the age of nation-states of the 19th century, and were

given the mission of producing a stable and uniform society.

Today, the style which has developed, mainly at the end of the

19th century, echoing up to the beginning of 20th century,

including individualistic American movements is wrapped up in the

worldwide phenomenon of Art Nouveau, which had the feeling of a new

individualistic architectural style at the fringes of the scattered

development of urban culture. It was as if the cities sought to become

separate and free from their nation.

If we look at the glass works of Emile Galle, irrespective of

earthiness of glass as a material, the fantastic microcosms that prompt

dizziness through the vagueness of the workpiece profiles and the

production of transmitted light rely solely on deep sensations developed

in the mind of the individual (Figure I-1). This does not have a lucid

structural theory, but is a world that can only be entered by artists

knowing the mysteries of art.

Even in the world of architecture, there are pieces like the

glass construction of Hector Guimard of melting cylindrical columns as

exemplified by “Castel Beranger” (Fig. I-2). The curved style of Art

Nouveau leapt forward by pursuing new shapes that ignored the forms of

the existing architectural schools. The grammar of ornaments of column,

which had been common sense in architecture, began to be ignored. If the

correct style of grammar was not used during the 19th century, the

architect would be scorned for having no learning, and that led to the

formalization of column decoration. The architectural aesthetics as the

learning of the bourgeois society began to be uprooted in the wake of

Art Nouveau.

Ornaments of column underwent a resurgence following a path from

the awareness of pursuing simplicity that had been the trend in the 18th

century to return to the Greek classic architecture. Finally, during

over 100 years of the 19th century, interest turned into spectacular

baroque, and architectural decorations including columns became complex

and excessive. The Art Nouveau columns of Castel Beranger were created

as even more splendid columns exceeding the elegance of these columns.

In other words, Art Nouveau was something that exhibited the extremes of

complexity.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the grammar of ornament in

the 19th century was completely ignored, and the Art Nouveau that marked

the starting point for this trend is not seen as the decadence of the

end but the youthful exuberance of the beginning. Art Nouveau was a

style that formed a turning point between two sets of differing values.

However, complexity came to be renounced at

the beginning of the 20th century, and Art Nouveau which was an extreme

of complexity soon lost its power in the wake of new tendencies. The

actors who play the role at the turning period are sad because they were

shunned by both the past and future and given nothing more than a

temporary period of peculiarity in the pages of history. In order to

assess the true meaning of Art Nouveau, we need to clarify the

mechanisms of the turning of styles, know the ecology of the style, and

demonstrate the large crevice in history brought about by a minor

phenomenon.

The fact that “complex systems” became a big

issue in the 1990s can be thought to be due to the action of the same

mechanisms. Although profound discussion on it is taken and placed at a

later stage of this book, in any case the current boom in oval shapes,

which could be said to be a taste of baroque, is thought to be

overlapped with the neo-baroque of the late 19th century, which was an

overnight phenomenon of Art Nouveau.

The “century” which forms the basis of the

phrase end of the century is a word that comes from the steps of 100

years in the ano domini, or Christian history. There is no reason that

time should be measured with the decimal system, and indeed the month is

following the duodecimal system. If the centuries were marked off

according to the duodecimal system, then there would be 12 squared,

which is 144 years in a century. However, there is no foundation for the

validity of the duodecimal system, the same as for the decimal system.

Speaking further, there is no reason for the birth of Christ to be the

beginning of the calendar apart from the believers of Christianity. It

was also not an absolute amongst the people of Europe, because it

is known that Revolutionary Calendar was attempted during the French

Revolution.

Thus the word “end of the century” is based

on such a vague idea that this word has no absolute meaning. Certainly,

because the phenomena at the end of the 19th century were decadent and

unique to a period of turning, they give a strong image. However, we

cannot say that the end of the 20th century is exhibiting the same kind

of phenomena. Furthermore we cannot say that there is no cyclic nature

in the history of mankind, on which we discuss in following pages. What

we now require is to clarify as a mechanism the process up to the

occurrence of decadent phenomenon like the end of the century.

(2) Fluctuating curves

Why is it that the colors and shapes of van Gogh, who is known

as an insane artist, continue to capture the eyes and hearts of people?

His representations that directly chase the depths of the psyche are

without peer, and are arts that could not be resisted including by us

Japanese. We know well how he got away from general society and fall

into insanity from his life story. However, is there not a need to try

to examine the mechanisms that gave rise to those paintings with

scientific means?

For example, let us examine the famous painting called “Starry

Night” (1889) kept at the

The bizarre fluctuation of this painting evokes association with

not merely the 1/f undulations, but also in general complex systems in

science today (Fig. I-4). The whorls covering the space link the

mathematics of chaos and fractal dragons with the fluctuating curves of

clouds that trace the mountain range. Many of van Gogh’s other paintings

are known to exhibit this kind of energetic curves.

The dot painting style of Seurat at the end

of the 19th century could be replaced by the rendering technology of

computer graphics that create colors by pixels today. On the other hand,

the painting style of van Gogh that creates energetic curved motifs by

overlapping short arcs can be said to be a dot painting with the

addition of motion. The method that is similar to the optical analysis

of Seurat is filled with artificial life motion by van Gogh.

As van Gogh began his artistic creation basing upon his own

peculiar religious feelings, we find vestiges of medieval religious

paintings with drifting spirits in the whorls floating in the sky. Of

course, he did not necessarily know the mathematics of chaos, and these

whorls exhibit an Expressionism of the unique psyche of van Gogh, which

attempted to show an unknown spiritual existence. Today, thanks to

attempts by scientists to analyze this, the phenomenon of vague energy

and matter has become unknown without being supported by the science of

the eye up to now.

Cezanne attempted to emphasize solids within a landscape, and

abstracted and Expressionism simple solids of buildings with sloping

roofs and pentagonal shapes, and the cubism of Picasso and others

developed from this. This is explained by the rationalistic scientific

psyche exhibited in the age. On the other hand, the scientific psyche of

van Gogh was of a type that did not rely on this type of classical

geometry, and only began to be understood at last by the complex science

of today. Probably simulations of the paintings of van Gogh are possible

to some degree by following fractal geometry, chaos mathematics,

artificial intelligence (AI) programs etc. using a computer.

In this way, the curved style of the end of

the 19th century was not merely the chance product of a single

individual creator, and there was some mechanism at work on some deeper

level. This is also common to the glass works of Garre and the

architectural works of Guimard and Horta, and is thought to represent a

new view on design. The fact that this kind of common phenomenon appears

in a variety of art is an evidence that something occurred deep in the

psyche of the people of this time.

Although the insanity was not as intense as

that of van Gogh, architect Antonio Gaudi lived with a similar psyche

formed from deep religious feelings. It is well known that from 1883

until he died in 1926, he not only worked almost exclusively on the

architectural design of the “Sagrada Familia” church in Barcelona, but

also attempted to realize his own devotions, including gathering funds.

The act of proposing and implementing a large-scale church by a single

architect is inconceivable without deep religious devotion. On the other

hand, in the modern age, this kind of devotion had been seen as a

remnant of the past. Gaudi’s actions must be looked within the context

of the time before modern.

Admirers of Gaudi’s architectural works are not limited to

Christians but also include many Japanese that are based on oriental

ideas even if it has become weak. In this way, the Sagrada Familia

church surpasses the realm of Christian religion and enters into

universality. This universality means not merely the perfection of the

work of an artisan, but also includes the modern sensibility of the age

of Art Nouveau.

The characteristics of the melting columns

that was shown earlier can be understood here for the Sagrada Familia

church, which is built with stone on the gothic style, as the melting of

entire church building made of stone. The plan type of basilica with a

forest of spires is clearly modeled on the medieval gothic style of

cathedrals. However, the planar outline gives variations to the strange

lines and is already not a true medieval gothic style. The shapes of the

spires are also bulging with splendor and modified to the vague outline

rather than that exhibited by the gothic structural beauty (Fig. I-5).

In Brussels in the same Art Nouveau, Victor Horta designed

progressive facilities for socialism called “houses of the people.” In

such period Gaudi was deeply committed to the ideas of Catholicism and

concentrated on religious architecture as if turning his back on the

modern age. For us in the second half of the 20th century, importance is

placed more on the style of the individual than of the period, and

therefore the feeling of existence of Gaudi has become even stronger.

But Gaudi who was obsessed with the medieval must be thought to be

against the age among contemporaries at the end of the 19th century.

Like the solitary and miserable death of Gaudi, artists that are

filled with genius today are made to feel this degree of weirdness.

However, the lifestyles of van Gogh and Gaudi show that they had a

common personality, and within the society that was rapidly flowing

towards the modern times the shape of the tortured artist must feel some

resistance to the flow within the depths of the psyche. This has the

aspect of the result of the psychological state developed in the age of

the end of the century being wrapped up smoothly within the individual.

Gaudi employed a dome construction in the design proposal of the

“Guell” church by creating a suspended curved surface by hanging a net

and inverting this (Fig. I-6). This highlights the scientific side of

Gaudi in his attempts at rational structural theory. From the standpoint

of modern rationalism that was the mainstream at the beginning of 20th

century, this can certainly be understood as indicating the aspect of

Gaudi as a modern man.

However, for example, the walls that are

wrapped in the weirdness displayed at Casa Mila cannot be said to be

something that can be interpreted using the same scientific theory, and

this is something with a deeper intuitive interpretation. This is said

to behold an organicism exceeding the scientific. However, analogy of

the organs of this living creature when applied to organic objects

displays the limits of the science of the time. It is because that

scientific theory has eventually created automatic machines but

bio-machines are still far-off. The idea of romanticism that exceeds

rationalism exists in organicism, and in its limits, organicism is

irrationalism.

The winding curves at Casa Mila or the

strange curves found at Sagrada Familia church were artistic pieces that

were made from manual work for the architect himself. This can be seen

as a shape that can be explained by fractal geometry or chaos

mathematics from our eyes. The interval of one hundred years has brought

about such a big step of age.

Art Nouveau curves can be thought of as the subject of science.

The chaos of the end of the century should be thought of rather as the

result of logical process following extremely the inclination of the

complexity than some degeneracies ore unknowable chasm.

(3) Collapse and rebirth of

style

The international Art Nouveau movement of the

end of the century flowed into the 20th century, and developed even more

in the first 10 years of the 20th century. In fact, the appearance of

Casa Mila was in 1910. From the Secession of Vienna, the appearance of

the “Post Office Savings Bank” of Otto Wagner, the chapel of Steinhof,

and the Darmstadt Artists Colony Museum of J. M. Olbrich continued even

after 1900.

The curved style of Art Nouveau was eventually passed on to and

expanded by the curved shapes of the German Expressionism in the 1910s.

The intermediary for this was the Belgian designer Henry van de Velde.

At the Cologne Exhibition of the Deutscher Werkbund (German Work

Federation) held in 1914 just prior to World War I, he exhibited

mysterious playhouse architecture where the edges had been rounded (Fig.

I-7). In the initial proposal where the Art Nouveau inspired curved

motif was placed centrally in the façade design, changes in the

conditions were prompted during the design process and this led to an

unexpected solid curved design.

In this way, Art Nouveau was inherited by Expressionism, opening

a new stage. However, Expressionism also quickly led to a dead end, and

is thought to have disappeared in the middle of the 1920s. There was one

person who knew that Expressionism was the embodiment of a new

complexity standing at the termination of the inclination to the

complexity that had been sought at the end of the 19th century. Although

Expressionism appeared as one of the movements that rejected the 19th

century and embraced the 20th century, this was not discontinuity but

the continuity somewhat like an insect shedding its skin for

metamorphosis.

The picture book published by Bruno Taut

titled “Der Weltbaumeister” (1920) showed the existence of this

emergence (*1). This was the story of the destruction of old

architectural styles and the birth of new architectural styles, and was

formed as a storyboard. As the act opens, gothic spires extend out one

after another from below. The structures of the over-extended gothic

cathedrals finally were unable to withstand their own weight and began

to collapse, falling down in a scattered heap of stones. Up to this

scene, there has been destruction reaching the stage of chaos (Fig.

I-8).

Now the destruction scatters dust through space much like the

big bang. Next, in the weightlessness of space, the dust begins to

gradually gather together, giving birth to a new star. Rain finally

falls on the star, which begins to overflow with vegetation. There

begins something to grow out from beneath the earth, and this is a

crystal house made of glass (Fig. I-9). This was the thing that sparked

the idea of the “Glass House” pavilion shaped like an onion head that

Taut himself designed for the Cologne Exhibition of the German Worker

Union in 1914.

The

first half of a scene of a mock complex of gothic cathedral is best

thought of as a symbol of the abundance of the neo-baroque period at the

end of the 19th century. The glass structure was thus the Expressionism

that appeared at the beginning of the 20th century. Although this also

had gothic style fittings, these resembled a Gaudi-styled Art Nouveau

flavor of gothic. The perimeter was enclosed by components resembling a

flying buttress, and vegetation-like curved surfaces could already be

seen here that were no different from the organic form of the life-like

Sagrada Familia.

From the end of the 19th century to the start

of the 20th century, the mark known as gothic played a large role.

Although it is known that the art historian Wilhelm Worringer

established a new research method to explain historical styles from a

deep level of psychology with the publishing of a book titled

“Abstraction and Empathy” (1908), this material took the form of

explaining that the vertical axis of gothic style was empathy. In the

same way as paintings were abstracted in post-impressionism,

architectural style began to be understood in terms of abstraction

rather than the details of artisans.

The gothic age did not seek the realism of

the Greek sculptures. Rather than accurately rendering the bulges of

naked sinew and skin, gestures filled with sorrow or religious devotion

were the ideal sculptured art, and deformed profiles were preferred.

Expressionism that are overly realistic did not transmit the inner

psyche. This was because the choice of an indistinct silhouette was

effective for correctly reading the beliefs. Although the religious

devotion of Gaudi was embodied by the undulating stone surface of the

Sagrada Familia itself, the wavering heart at the back must be noticed

without the eye being captured by the mysterious walls where the thing

that is rendered cannot be understood.

The German word “Zeitgeist” (the spirit of

the age) became a buzzword at the start of the 20th century. This word

came to be viewed as a symbol for the time and came to be used in the

English language as a loanword. The vertical style of gothic was an

Expressionism of the Zeitgeist of the people of the middle ages, and

there were arguments over what kind of Zeitgeist should be held for the

people of the 20th century in the same way. It was the age when the

spirit, something abstract in the depths of the psyche, was asked for.

Taut thought that the gothic spirit appears

more clearly after extinguishing the detailed decorations of the gothic

cathedrals, and brought about the appearance of the abstract glass

gothic. Immediately after the World War I, he called on architects and

artists and promoted a Utopian movement. As a standard for this, he

suggested the gothic cathedral that was constructed from hard work and

hope for a secure society by the medieval artisans. Taut borrowed the

shape of the gothic cathedral as a monument that joined the strength and

psyche of people. There was Taut who was an architectural theoretician

of reformative social democracy, called also as an syndicalist (trade

unionist).

The symbol of the gothic cathedral of Taut

morphed into the declaration to establish the Bauhaus of Walter Gropius,

and is well known to have been Expressionism in the frontispiece of the

gothic cathedral drawn in the cubism style and Expressionism style by

Lyonel Feininger (1919) (Fig. I-10). The declaration to establish the

Bauhaus was written as follows.

“Let us together dream of, conceive, and

build the new structure of the future, … that will climb up towards the

heaven as a crystal symbol for the new coming belief out of the millions

of hands of artisans. (*2)”

This was the desire to newly create and change the classical

gothic cathedral as a symbolic monument that was suitable for the age of

mass society. It pursued the same plot as the drama of destruction and

rebirth proposed by Taut. However, this was not actually done to give

birth to new and changed structures, but was supposed to bring together

a new Zeitgeist of the time and give birth to a new and changed society.

The architectural style was nothing more than a symbol of society.

In Taut’s “Der Weltbaumeister”, two stars

born in the midst of the darkness of space are drawn as becoming

mutually entangled like in a dance, and this exhibited the organic

motion like an image of chaos drawn together by an attractor (Fig. I-11,

12). Although the fragments of rock that lose their mutual relationship

after a brief collapse become chaotic as an aggregation of simple dust,

it showed the organic chaos like the phenomenon of life. The evocative

forms of Expressionism are generally interpreted as the manifestation of

an inner desire seeking for an outlet under gloomy societal conditions,

and the organic personality of the phenomenon of life is expected to be

seen to exist here. In other words, this could be said to be organic

chaosism.

The prosperity of the later part of the 19th

century caused the transformation into conditions of an overabundance of

buildings through eclecticism and neo-baroque, and these could not

withstand their own weight, leading to self-destruction and an inorganic

chaos like a heap of rubbish.

Then organic chaos appears again giving birth to a new life. The

phenomenon from the end of a century to the beginning of a century is

this kind of drama of destruction and rebirth. It was the phenomena that

separate the trends of the major ages, equivalent to the drama of

destruction and rebirth like the transition from the late gothic to the

start of the renaissance or that from the late baroque to neoclassicism.

Art Nouveau and Expressionism, which seem temporary phenomena were not

merely random fashions, but were the footprints of the competitive

development of the chaos phenomenon that took the opportunity of the

strategic point in history.

(*1) Bruno

Taut, "Der Weltbaumeister", Hagen, 1920.

(*2) Toshimasa

Sugimoto, “Bauhaus”, (Japanese) Kajima Shuppankai, Tokyo, 1979, p.41.

2. Recurrence

to classicism and abstract geometry

(1) From Art

Nouveau to neoclassicism

The transition of Art Nouveau to

Expressionism was a steady process of development on the themes of

complexity and chaos from the stage of the excessive style decorations

of neo-baroque to the vegetation-like two-dimensional curved style and

then to a three-dimensional curved style. This transition process is

nothing more than displaying one side of the period from the end of the

19th century to the start of the 20th century. This was destined rapidly

to reach the extremes of chaos, and eventually end in the midst of

narcissism. Therefore, a new vessel was prepared for the people who

dislike a sinking ship.

This was a rejection from the roots of the theme of complexity,

and strove to take a theme aspiring for simplicity. If we look back in

history, the transitions from late gothic to early renaissance and from

late baroque to neoclassicism are actually the same phenomenon of a

switch from the theme of complexity to the theme of simplicity. The

start of the 20th century was a schism of ages. On one hand, the flow to

art nouveau was preceded by attempts to expand to even further

dimensions, while on the other hand, there was a departure from that

flow.

Ten years after the passing of the end of the

century was a time that could not be categorized neatly using a single

word. This was a time where the remnants of Art Nouveau and the leading

edge of modernism that followed the 1910s were separately and

independently active. This can be said to be a period where two styles

competed and ran in parallel while grasping an entanglement of

complexity and simplicity.

The key person of this period was Peter Behrens who turned from

Art Nouveau to neoclassicism.

In the 1890s, he excelled at floral curved motifs as a painter

of Jugendstil, the German version of Art Nouveau. He was perhaps also

influenced by Ukiyoe, and also created unique block prints. He was given

the opportunity to design his own residence in

From around 1904, he completely discarded the curves of Art

Nouveau and replaced the tenets of clear-cut vertical and horizontal

lines with geometrical volume. Why this change occurred was not clearly

stated. Although something clearly came up at a deep level of his

consciousness, the about-face was decisive. The interior design of the

restaurant “Jungbrunnen” at the

This change cannot be seen merely as a

personal episode. The reason is that actions of Behrens after this

became a vehicle that led the 20th century. In 1907, the major

electrical corporation AEG invited him to

The “AEG Turbine Factory” (1910) designed by Behrens is famous

as an epoch-making structure in the history of modern architecture (Fig.

I-15). This gave the architecture of the factory, which was a simple

work hall, the external appearance of a temple, and gave it the status

of a legitimate building. When we speak of a temple-like appearance,

this was not like rows of stone-created columns like in the Greek style,

but replaced with I-shape cross-sectional steel beams that gave the

certification representing a new aesthetic to the steel skeleton.

Instead of the pediment of a triangular gabled roof in the front, the

pediment displayed the multi-angular arch roof shape of the steel

skeleton as is with rounded bands.

The change of tenets of Behrens gave

geometrical forms to all shapes. Although he had the ability to design

the freely curving surfaces of Art Nouveau, his intention of

self-restraint was solid. In particular, the tensile relationship

between columns and beams that referenced the styles of classical

However, this did not initially focus only on Greek and Roman

classical styles, but also used Romanesque styles. This was not simply a

variation of the style, but was because the architectural style of the

Romanesque period was often based on geometrical order. Romanesque was

the first complete style after the great migration and settling of the

Germanic people in Europe, and it held a unique structural spirit that

the Germanic people are thought to have held dear even before the

migration period. This preferred rectangles and continuity, and the

building of the whole by combining several basic solid elements such as

wood block construction, as exemplified by St. Michael’s church in

In other words, Behrens returned to the roots of the structural

spirit of the Germanic people, and caused the rebirth of a geometrical

sprit. If we say this, then although it will probably sound like nothing

more than a problem of ethnicity, this kind of structural spirit of

origins often arises throughout history, and gives birth to a breath of

fresh air in the period. This was apparent in both the northern

renaissance, and the neoclassicism of

In the “Kunos mansion” that Gropius

contributed as an office worker, there were significant aspects that are

thought to be this kind of Germanic geometry (Fig. I-16). The external

appearance is formed from a simple single parallelepiped, with a

cylindrical stairwell incorporated in the middle of the front face. The

basement is packed with rubble and the eaves molding is clearly defined,

and although it is like the simplification of renaissance architecture,

detailed style decorations cannot be seen. The external appearance

features a continuity of sharp virtually square windows cut into

undecorated white walls.

Gropius eventually realized the new

architectural style of a four-dimensional style in the design of the

“German Worker Unit Cologne Exhibition Model Office and Factory” (1914),

which fitted all glass-walled cylindrical stairwells on the right and

left ends of the parallelepiped main room with transparency, allowing

people ascending or descending the stairs to be visible (Fig. I-17).

Thus, the Expressionism with the cylindrical stairwell gained from the

Kuno mansion was utilized here. If we go back, Romanesque churches often

featured two or four cylindrical towers arranged in pairs and were

created with a unique appearance of wood paneling, and although only

weakly, the vestiges here emphasize the well-spring of the Germanic

structural style.

The philosopher Ernst Cassirer attempted to

explain the structure of the psyche of German people by the style of

“freedom and form” (*1). If the conversion of Behrens from Art Nouveau

curves to neoclassical geometry is understood by the former representing

the aspect of freedom and the latter representing the aspect of form,

then the German people have two spirits that can be Expressionism in a

single person. For example, as can be seen in the designs of Kenzo Tange

which exhibit, on the one hand, the dynamic curving shape of the Yoyogi

Olympic Gymnasium, and on the other hand, the geometrical beauty of

Within the flow of a period of

development from fragments and Art Nouveau to Expressionism and the

development of aspiring towards the neoclassical geometry that was a

rejection of fragments and Art Nouveau, Behrens was sensitive to the

transitions in the world of structure, and utilized the power of the

shapes that symbolize the zeitgeist in response to the changes in

society. As an artistic advisor in a large corporation, the industrial

design of factory design, worker collective accommodation design, and

fan and lighting design opened new areas of activity for artists while

he bestowed aesthetic honor upon the modern society. His conversion from

individualistic and free hand operations of Art Nouveau to the design of

geometrical systems in the spaces requested by society was ultimately

the demand of the times, and Behrens focused himself on the style of the

age and the society even more than an individual style.

(2) Cult of Greece and

inclination to simplicity

The post-modernism of the 1970s to 1980s had the fashion of

incorporating Doric columns, etc. into new designs. Among this, in the

competition for the “

Thus, the Loos of the time was a person who

was a perfect stranger to the pleasures of the post-modern styles. The

Doric column is not a sensuously enjoyable thing, but is selected as the

result of strenuous architectural theory. For Loos, classical

“If looked at it like this, it is clear that without exception,

the successful architects are not the most flattering to the period, but

are the people who stick to a classical standpoint without worrying

about the view of other people. … Therefore, some degree of eccentricity

is natural and required. That degree, both presently, and (…) in the

future, is without doubt classical

Based on this belief, although Loos had examples of large

columnar Roman monuments such as the pillars of Emperor Trajan of

classical Rome, there were no examples of Greece, and somebody must

realize this somewhere at some time. The Chicago Tribune was for this

reason, and employed a Greek column in order to best Expressionism the

commemoration of architectural style.

Returning to the middle of the 18th century, there was a

resurgence of Greek style as an ideal architecture. At that time, the

architectural styles of the late baroque and rococo, which were

overflowing with decoration were in fashion, and the new efforts in

preference of Greek style both waved the flag of “simplicity,” while

severely criticizing the fashions of the time and the baroque style of

Michelangelo (*3). This highlighted the origin of Greek inspired

architecture, and thereafter the architecture degenerated by the

imagination of unnecessary and excessive decorations. The idealization

of

The behavior of Loos also took in the same features. In the

beginning of the 20th century, Loos again attempted to restore the

strict theory of neoclassicism of the 18th century. Doric style was the

oldest even among the three Greek orders, and because it was thought to

represent the origin, Doric style was needed over Ionic or Corinthian.

Therefore, the trouble of using classical

Greek style in the modern age of the 20th century was unavoidably viewed

as anachronism from a third party viewpoint. Although classical

restoration has a particular meaning, a mechanism exists more than the

simple reference to historical treasures. One is re-confirming the pure

principles at the starting point by tracing back to the source, and

another is finding eternal principles that outlive time.

Since the time of enlightenment of the 18th century, in place of

the previous dogma of the church and commands of dukes, scientific

rationalism was thought to be the principle on which society was built.

In order to secure that rationalism, both the indication of the source

and demonstration of eternal invariance had a role. Bringing forth a

challenge to the classics is an important means for explaining modern

rationalism. Although at a glance there is a mismatch between retracing

the past and the modern existence, there is actually a tight connection

in the background. The neoclassicism of the 18th century that studied

Greek temples in detail as the ideal architecture actually meant to open

up the age of the modern by this kind of mechanism.

Loos’s proposal of a Doric column-style high-rise building had a

link to the aspirations to the future of modernism. However, the thing

that was the most effective in this kind of logic was the single digits

in the 1900s. With the rapid changes in architectural styles, by 1922

when the

Although

Loos harshly condemned this kind of architectural style with an

excess of decoration as an act resembling a “criminal.” The Doric

column-style high-rise building was proposed based on the idea of

ensuring the monumentality while simplifying by removing the

subconscious decorations. However, the theory of that simplification was

undertaken by the next generation of Gropius and others. Therefore, the

thing that was useful in the cutting edge purity of Loos’s theory was

only in the time of the single digits of the 1900s. In fact, Loos’s

speaking and writing activities started in the 1890s and extended into

the 1900s. In 1910, he built virtually undecorated urban architecture

that attracted a scandal and was later known as “Looshaus” in

Michaelerplatz in

One method of information aesthetics related to computer

technology reproduces forms on a display and the amount of information

is determined by the amount of data required for this. Structures of

pyramids and pure parallelepipeds have a small amount of information. In

a three-dimensional coordinate system, a line is created simply using

the XYZ coordinates of two points and the command to join them.

Rectangular planes consist of four coordinates and four lines, and a

specification of the front and back of the closed surface.

Parallelepipeds are formed from six surfaces. With only this amount of

information, volume can be reproduced.

However, as detailed decorations are added, solid information

needs to be defined for each of the small shapes and the amount of

information increases in a burst. A large amount of computer operating

time is also required for the reproduction. The neo-gothic architecture

of Hood, etc. would require a massive amount of information. Of course,

the cost is not necessarily directly influenced by the magnitude of the

amount of information. Pyramids which are notable for the small amount

of information also invite feelings. Loos who advocated removing

unnecessary decoration could also be said to be reducing the amount of

information. The clear adversity that arose between the aspiration for

complexity and simplicity can also be understood from the viewpoint of

modern information aesthetics.

“Economy” was one of the big themes of

neoclassicism of the 18th century. The meaning of this word at that time

can be understood more easily if interpreted as thriftiness rather than

economics. This economic concept gave birth to standards in

architectural design of it being acceptable to remove decorations if

there was a shortage of funds and leave plain walls exposed. In fact,

against the background that emphasized heavy architectural styles with

little decoration as shown by the architect C. N. Ledoux around the

French Revolution, architectural styles are used that omit decoration in

local architecture that does not specialize in elegance.

Loos used his residence in

If there were no decorations, the cheap architecture had no

splendor. Loos had aimed to give a sense of proportion to the

undecorated structures as learned from classical architecture, and in

fact, the undecorated structure like Steiner House has hidden horizontal

and vertical regulating lines and has beauty of proportion in the forms

of windows.

(3) Abstract classicism

The

The architects of modernism were proponents

of a break from history and aimed to create completely new shapes by

aspiring not to find models in history. However, things did not proceed

so easily. Colin Rowe clarified that the designs of Le Corbusier had

roots in the Palladio Villa architecture of the 16th century (*4). Thus,

although Gropius and Mies relied heavily on architect K. F. Schiknel who

left many structures in

It is also not widely known that from the 1910s to the 1920s,

they Expressionism a large change in style. As described earlier, the

1900s was the time of 20th century neoclassicism by Loss and Behrens,

and both Gropius and Mies learnt the practical details of architecture

during this period. Thus, their time started from the 1910s. These two

who had been taught by Behrens obviously threw themselves into the flow

not from Art Nouveau to Expressionism, but the flow to neoclassicism.

The debut of Gropius in the 1910s was spectacular, but Mies was somewhat

slower perhaps due to the

depth of his thoughts.

At the architecture office of Behrens, Mies was given the

responsibility of designing the “German Embassy” built in

The eye-catching style of this weight

developed into the “Bismarck Monument” submitted by Mies in 1910 as a

member of the Behrens office, and his unique style became clear (Fig.

I-20). Although the proposal was for a huge platform to be built on a

plateau beside the

After this, Mies moved to

Mies was raised as the son of a stone mason, and is thought to

have been familiar with stone materials as a child. In the 1910s before

he had been influenced by modernism, he searched for conventional design

motifs. The neoclassicism of the 18th and 19th centuries faithfully

followed the Greek forms on one hand, and were relatively symbolic of

their representation of the strength held by columns and beams on the

other. For example, structures like the Villette gate of Ledoux (Paris)

used unsophisticated structural forms with almost no classical

decorations as is for architectural Expressionism. The

In the case of Gropius, he inherited the

clear-cut geometry used in the

Furthermore, the farmhouse for two families

(Janikow, 1906) designed by the 23-year old Gropius immediately before

he entered Behrens office had already well displayed the heart of

Gropius. The outlines were symmetric, with eight vertically tall windows

arranged along the first floor, and two second floor windows each

arranged to match these on the left and right. The left and right ends

held a fireplace, chimney, and entrance. This showed similarities to the

undecorated walls of Loss and orderly window placement (Fig. I-21). The

symmetric and ordered design of the window placement had a pediment

added to the 1914 Dahlberg warehouse structure and showed a Behrens-like

templar motif.

Then, in 1914, Gropius and Meyer arrived at the epoch-making

work of the model office and factory using large glass panes, exhibited

at the Cologne Exhibit of the German Worker Union. This has come to be

seen as leading each of the modernist architecture style that was to

follow, and if we forget to interpret it from the viewpoint of the

1920s, the extension of that tradition emphasizes neoclassicism.

The model factory had a facade outline that

was pentagonal shaped with rounded corners, and was a rationalization of

the AEG Turbine Factory of Behrens that was rooted in classical temples.

On the other hand, the model office was formed from a simple

parallelepiped resembling the farmhouse

for two families at Janikow, with protrusions on the left and right

sides of the main face and orderly division of the brick walls. On the

other hand, the reverse side had an array of columns on the first floor

and full-pane glass on the second floor divided orderly by steel. Apart

from the array of columns, almost no classical style decorations can be

seen, and the external appearance is divided by the clearly modernist

horizontal and vertical lines.

The revival of classicism in the 1900s gave rise to abstract

shapes as neoclassicism without the classical decorations by Mies and

Gropius in this way. Although this is certainly influenced by the shapes

that predicted the 1920s, the symmetry, facade division, and column

array motif of premodernism remain as elements, and show a transitional

personality.

Although Art Nouveau and Expressionism developed with the free

feeling of searching for undiscovered forms, the trend of the formal

beauty of neoclassicism sought an abstentious simplicity. By the

forefront of the two flows of the early 20th century, the 19th century

rapidly receded into the past. The means for handling the main turning

of the ages and the motion of that mechanism is clear: Pursuit of an

abundance of total freedom or the return to transparent formal beauty by

decreasing the amount of information. Although either path was possible,

a feature of this time was the incompatibility between these two paths.

(*1)

Ernst Cassirer, “Freiheit und Form”,

Japanese translation by Hajime Nakano, Minerva-Shobo, Tokyo, 1972.

(*2)

Adolf Loos, “Ornament und Verbrechen”, Japanese translation by Tetsuo

Itoh, Chuou-kouron-Bijutushuppan, Tokyo, 1987, pp.48-49.

(*3) Toshimasa

Sugimoto, “German Neoclassicism Architecture”, (Japanese) ,

Chuou-kouron-Bijutushuppan, Tokyo, 1996, pp.31f.

(*4) Colin

Rowe, “The

Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays”,

Japanese translation by Toyo Ito and Yasumitsu Matsnaga, Shokokusha,

Tokyo, 1981, chapter 1.

> BACK