> BACK

revised on

2010.10.16

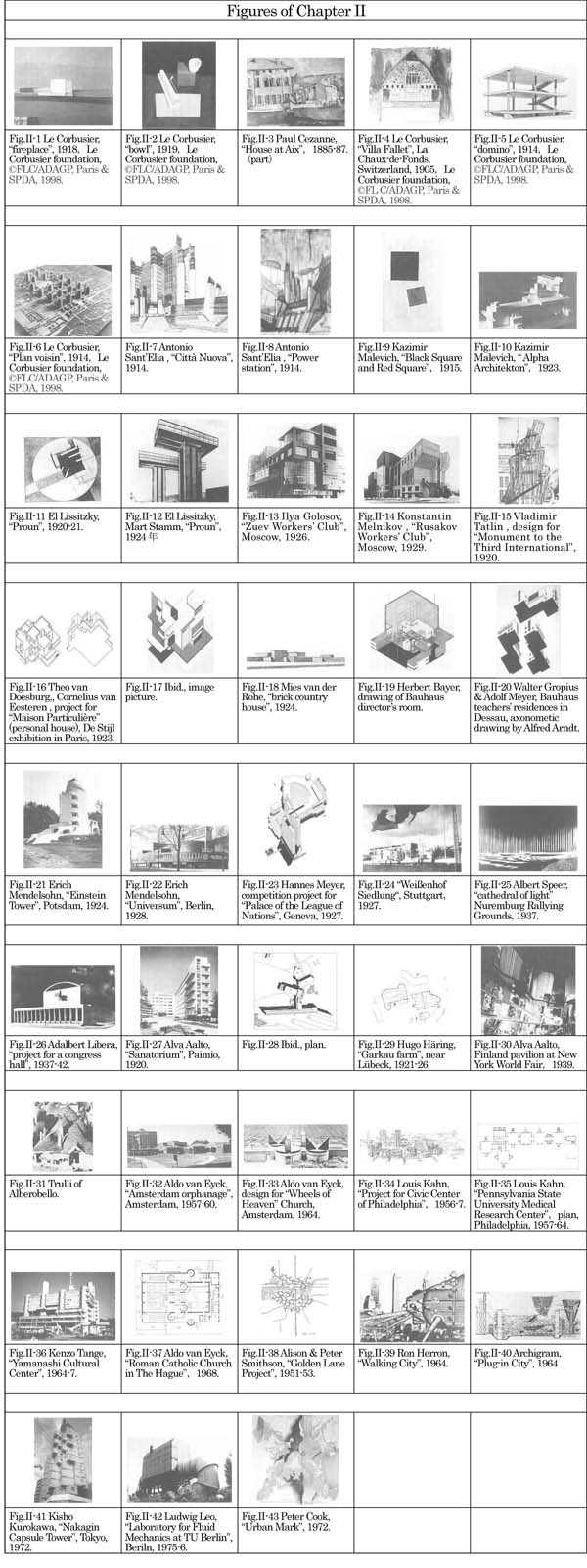

II. Adventure of Reason

3. Construction from zero

(1) World view of Purism

At

the end of World War I in 1918, Le Corbusier started the Purism movement

together with Amédée Ozenfant. Le Corbusier debuted as a painter at an

exhibition at the

The

thing that catches the eye is a white cube in the center that appears

like Japanese tofu(bean curd). Classical console decoration is visible

in the lower left, and it can be understood that this is definitely

located above the fireplace. However, there is no clue to identify what

this cube was drawn to represent. Furthermore, there is shading and

reflections on the mirror-like top of the fireplace. Because of the

realistic scene, it has the mysteriousness of a

Surrealism

painting.

In

the same year, Le Corbusier and Ozenfant wrote a book entitled “Après le

Cubisme” (“After Cubism”), which attempted to be the critical successor

of the Cubism artistic movement. Cubism carries the new sensibilities of

the 20th century to geometrically disassemble the three-dimensional

spaces that can be seen using the eye, and pioneered a method for

redrawing abstract paintings. However, Le Corbusier and others thought

that Cubism continued to fail in the mannerisms of the method. Le

Corbusier sought a new reality.

Although a cube also appeared in the painting entitled “Bol, Pipes, et

Paipers Enroulés” (“Cup, Pipes, and Paper Rolls”), the trend toward

abstraction was more clear in this case. There are curled up rolls of

paper, pipes, and a white pottery cup on top of a cube arranged on a

table, and these are clearly represented by abstracting a realistic

scene (Fig. II-2). However, the identity of the brown cube that appears

like it could be a box placed there is unclear. There is also deep

interest in the dangerous positional relationship that raises concern

over whether the cup might fall off from the cube.

Le

Corbusier seems to have returned Cubism to the straightforwardness of

Paul Cezanne. As can be seen in paintings such as “House at Aix” (“Maison

et ferme du Jas de Bouffan”, 1885 to 1887), Cezanne abstracted the plain red brick house that appears

in the middle of the scene to the point where it is barely discernible

as a house. He was the first painter to start with piecework-like

elements (Fig. II-3). Although Le Corbusier gradually increased the

level of abstraction, this did not develop to the point of virtually

discarding any connection to the real object, as Picasso had done. The

fact that he was not purely a painter but was also an architect demanded

a realistic space even within the painting space.

In spite of this, his cubes

remain mysterious. This is the same as the mysteriousness of the

pyramids of

Of course, this knowledge was

hidden when abstract shapes were used in architectural designs. The

abstract shapes do not necessarily have psychological power. Although

functional structures such as factories have clear ordered patterns,

normal factories do not stand out. Intentional stylization such as the

temple motif given to the factories by Behrens was required for this.

Although Le Corbusier stayed at Behrens architectural offices in search

of something, it became clear after looking for a while that there was

little to be gained, and the forms sought by Le Corbusier were slightly

different.

I introduced the basic idea of

information aesthetics earlier, and that also plays a role in the

interpretation of what Le Corbusier was trying to obtain through Purism.

He knew that the objects that we can actually see with our eyes contain

too much information, and some alterations were needed to reduce the

amount of information in order to convey or represent something. Cezanne

certainly did this, and Le Corbusier clarified the validity of the

origins of Cubism. But for the painter of Impressionism, it was

important that the outer world is reflected in the eye, that is the

phenomenon of “im-press” against the heart. On the other hand, Le

Corbusier must create the form of a house in a vacant space as an

architect, where his painting work was nothing more than preparation for

it.

For an architect, the job is to

create information. The forms created must contain an abundance of

information. The mysteriousness that can be seen in the cubes in “La

cheminée” and other paintings is because the shape created by 8 simple

points and 12 edge lines is imbued with psychological information in

addition to physical information. The first 20 years or so of the 20th

century was a time when the drive toward simplicity began, and Le

Corbusier attempted aggressively to manifest the power held by simple

items as an extension of this.

The word Expressionism specifies

the artistic action of “ex-press” that is to push out to the outside

world. Although the mode of expression of the strong impetus of German

Expressionism was evident from a peculiarly expressive intention, the

artists of the early 20th century aggressively generalized the

construction of objet d’art (works of art) and spaces. If we take a form

of Expressionism that attempts to express everything merely by the

silhouette of a shape, then there is also a path that achieves

expressive power like that of the pyramids through the simplification

and transparency of shapes similar to Le Corbusier. In any event, the

time where groups of excessive and chaotic shapes were a means of

communication became a thing of the past.

The first building “Villa

Fallet” built by Lu Corbusier in the town of La Chaux-de-Fonds, a watch

handworker’s town on the North side of Lake Geneva where he grew up, was

packed with a variety of information, including the steeply inclined

wooden roof, construction with the traditional curved braces, the design

of the window frames that symbolizes a tree-like structure, and the

fresco-like decorations with a repeating-pattern-like wallpaper (Fig.

II-4). This revealed a light and gentle design that could be called a

slightly girlish extension of simple conventional construction methods

without the excesses of neo-baroque or the organic curves to the degree

of Art Nouveau. He was strongly affected by Cubism that led to the

extreme of abstraction, i.e., the reduction in the amount of

information. This was because cubes without any meaning were the extreme

of virtually zero information.

Before the declaration of

Purism, Le Corbusier presented the principles for an architectural

pattern named Dom-ino in 1914 (Fig. II-5). This showed that the skeleton

of a building could be formed if the floor was supported by only four

concrete columns, and only required the foundation slab (the surface in

contact with the ground) and stairs for buildings of two or more

stories. The revolutionary point of this idea was that it reversed the

idea of the traditional brick construction method in Europe, where

construction of brick walls started first, with the construction of

internal wooden beams and floor being added later.

The walls were added later, and

the full glass surface architecture that came much later was derived

logically from this. Although it was simple, this architecture was a

reversal of the conventional knowledge of the past and had to pass

through a variety of strife before it became generally accepted.

This spirit was common to

Purism, where unnecessary information was cut away and objects were

reassembled from the remaining minimum elements. In the several years

from Dom-ino until the announcement of Purism, Europe slid into

political and social chaos, with World War I intervening, which turned

common sense on its head. During this time, the Russian Revolution

occurred, followed by the German Revolution at the end of the war, with

the Czars and Kaisers expelled and the society of

Eventually, Le Corbusier

proposed a plan for reforming the city center of

There was a view point to clear

away existing information created through the accumulation of history

and to rethink a city from nothing. This type of method to destroy

existing buildings at first and to redesign and redevelop a completely

new design forgetting the figure of the past is called generally “scrap

and build,” and has spread throughout the world particularly since

postwar reconstruction after World War II, whose idea was brilliantly

here. This kind of methodology is also called “Tabula Rasa (blank

slate),” and the spirit of modernism existed within those action itself

of erasing existing things.

Dom-ino, the idea for which was

sparked from thin columns and floor boards, represented a complete

disavowal of traditional European architecture and logical rethinking of

only newly produced building materials. Although a tradition of wooden

construction also continued to survive also in Switzerland where Le

Corbusier grew up, this is conjectured to have also the hidden effect of

the Japanese wooden frame construction that was assumed to have affected

the architects of Europe. We can find here one of actions worthy of

respect that the European people themselves disavowed the traditions of

Europe and attempted to begin again from zero.

(2) Breakthrough of Futurism

In

the same year of 1914 when Dom-ino was introduced, Antonio Sant’Elia

published the “Futurist Architecture Manifesto.” The “Futurist

Manifesto” was published by the poet Marinetti in the paper “Le Figaro”

in 1909, and took the artistic world by storm. The content of this

manifesto was also a disavowal of traditional Europe by Europeans

themselves.

At

this time when the phrase “Decline of Europe” was exchanged between

intellectuals, Europeans actually largely followed the path of

transforming into people of the world. The International Style that was

subsequently established focusing mainly on German style in the 1920s

spread throughout the world, beginning the spatial culture of the 20th

century. The decline of Europe meant the new domination of the world.

This domination was not through a struggle for political power or

hegemony, but was through the establishment of people’s ordinary

lifestyle.

Europeans struggled in order to transform themselves into global

mankind. For example, van Gogh and Gauguin searched the Orient for new

ideas, the paintings of Cubism referenced the primitive engravings of

Africa, and architects referenced the vernacular architecture of the

Mediterranean coast and wooden architecture of Japan. The thinking of

the Europeans had already exceeded the bounds of

It is said that it happens

sometimes in history paradigm shifts where the ideas of people are

switched from the base. Historical architectural styles can also be said

to be paradigms; for example, the Gothic and Renaissance styles differ

in their origin with regard to the manner of thinking and the method to

construct thinking system. Europe in the early part of the 20th century

attempted a similar shift; however, the architecture of the new paradigm

was not limited to

The disavowal of the current

state of Europe brought about the exotic romanticism of yearning for a

barbaric world on one side, and it raised also the romanticism of

dreaming the future on the other side. Futurism expressed the disavowal

of the current status quo by proposing an image of an unknown future

society. Sant’Elia wrote the following:

“We must invent and rebuild the Futurist city like an immense and

tumultuous shipyard, agile, mobile and dynamic in every part, and the

Futurist house must be like a gigantic machine.

(*1).”

The image of 19th century

architecture, such as the abundance of decoration in neo-gothic, was

harshly criticized, and mechanisms like shipyards or machines without

the scent of culture become the new model. This change ignored history

to the point where it could be viewed as a barbarization of culture. The

architectural culture of

Sant’Elia drew many plans

entitled “Città Nuova” (“

The writings of Sant’Elia were

revised by Marinetti, the leader of Futurism, and it is here that poetic

expressions were introduced.

“That oblique and elliptic lines are dynamic, and by their very nature

possess an emotive power a thousand times stronger than perpendiculars

and horizontals, and that no integral, dynamic architecture can exist

that does not include these;

(*2).”

Sant’Elia selected and used

sloping lines like a hydroelectric power dam for the shape of the future

city, and Marinetti perceived these as a figurative symbol of the future

city. The elliptically shaped lines obviously referred to parabolic

curves of some structural lines. If this is said to be superior due to

the shape born from structural certainty, the artificial aesthetics of

classicism are ignored. The traces of the handwork of human were

completely removed.

The anti-humanism of Futurism

advanced to such an extreme that it became laughable. They became

enthralled by the appearance of the modern warfare technology that gave

birth to the the machine gun and tank. And with the outbreak of World

War I, they volunteered to appear in the field of combat. For them,

compared to the lethargy of the everyday, the feeling of speed of the

war was nothing more than ecstasy. Sant’Elia, who was blessed with an

abundance of imagination and was expected to be the arrowhead for the

appearance of a new architectural style from

Even now, although they are said

to have been fairly self-destructive artists, this was a consequence of

Futurism attempting to destroy their own European culture. They were not

simply future Utopians who saw sweet dreams and drew the form of a

bright future city. They stood at a turning point in history and

attempted to change history by their own resolve.

The ideas of the urban and

architectural theorist Paul Virilio, who gained attention in the 1990s

taking the concept of a “speed” as the key term, started from this

Futurism. The idea of creating an awareness of speed in architectural

design was inconceivable against the setting of 19th century

architectural forms. Sant’Elia therefore discovered the perspective of

the passengers of electric trains and automobiles, and understood the

new order of things, which differed from the architectural order

reflected in the eyes of pedestrians. The 20th century was not only a

time of super-high speed trains, but witnessed the introduction of

machines with more speed, from the jet engine to the rocket, and even

today, the Internet has come to carry information virtually instantly to

the other side of the world through optical technology. Virilio said

that this has changed the psychological and behavioral patterns of

people, and has had an effect on the structure of society.

This yearning for the inorganic

order of high-speed machines was also the product of humanistic designs,

like the poetic sentiment that enveloped the sloping lines of Marinetti.

The sketch of the “Electric Power Plant” by Sant’Elia showed curved

lines like smoke wavering in the sky (Fig. II-8). These are unmistakably

Art Nouveau curves, and the designs of Sant’Elia were greatly affected

by Art Nouveau. On the ground, a rational ordering was put together that

was constructed almost entirely of straight lines. Then, when the

feeling of speed of these straight lines raised up into the sky, these

became the curves of Art Nouveau.

The curves of Art Nouveau,

however, were the seeds that led to the futuristic feeling of speed. The

curves that melted and then organically drew together the chaos of 19th

century forms of architecture were the beginning of the subsequent

fluctuating spaces. This was also an extension of the mysterious

fluctuation curves wriggling in the sky, as seen by van Gogh. From among

the chaos of the end of the century, the organic chaotic curves were

gradually drawn out.

The elegant feeling of speed of

the Art Nouveau curves shifted into the abrupt feeling of speed of

mechanical straight lines. The pleasure of curves dancing in space

eventually shifted to the feeling of speed and arrived at a linear

structure. The shadows of romanticism that remained in Futurism were

eventually eliminated, and the warmth from the touch of the artist

discarded, with the movement moving into the cold form of rationalism

that could be discussed later. This move was also one of turning points

in order to enter into the 20th century.

(3) Constructiveness of Constructivism

The Russian and Dutch

Constructivism movements grew into a 20th century architectural style,

expanded into other schools, and left behind a large impact.

“Kosei-Shugi” is usually used for the Japanese translation of

“Constructivism”, but it is not adequate, because “Kochiku-Shugi” is

better when translated literally. But it may be meaningless to focus on

minor differences, because it was the age of fluid movement.

In Japanese, there is a fairly

large difference in fact between “Kosei” (“to assemble and compose”) and

“Kochiku” (“to construct and build”), and the Russian Constructivism

matches the word “Kochiku” better, while the Dutch Constructivism had

the meaning of composition and was closer to the word “Kosei”. Although

these are minor differences, the Russian Constructivism had a connection

to the Russian Revolution and included the meaning of building from

zero. On the other hand, Dutch Constructivism emphasized the abstract

formal structure appearing from among the traditional geometrical

mysticism.

A similar formative process with

a slightly different foundation appeared, and this gave birth to the

Constructivist style across Europe, called International Constructivism.

This was not simply a fashon of forms, but was linked to a new reality

of shapes. The activities that had been limited to a formative movement

under the introspection of the initial artists eventually established a

rational formative language for structures and urban design.

This was related to the

rationalism of lifestyle of “New Objectivity” (“Neue Sachlichkeit”) and

functionalism of the 1920s. There was constant argument over whether art

played a role in the everyday life of people and remained as an

outstanding achievement. Although art is certainly always contaminated

by impurities if we focus on the utilitarian, it is also clear that art,

which is isolated from lifestyle, can only be an escape from human

society. In any case, for architects, Constructivism came to be employed

as an extremely useful formative technique in the establishment of 20th

century architectural styles.

Also among Russian

Constructivism, there was an artist who focused his efforts on

discarding the styles of the late 19th century and turning towards the

styles of the 20th century. It was Kasimir Malevich, who created the

school called Suprematism.

He originally appeared as a

regional Impressionist painter, and eventually appeared in

However, the robust psyche of

Malevich peered into the depths of the European-scale abstract painting

movement. This was because the “black square” (1914-1915) where he

experimented with drawing a simple square on a square canvas, and the

philosophically titled “white on white” (1918) where he experimented

with drawing a diagonally leaning white square (Fig. II-9). The Russian

Revolution then intervened, and Malevich was led to the point of

absolute zero in the world of painting, as if he had felt and absorbed

the strange psychological state of society.

In the world of two-dimensional

computer graphics, i.e., “painting software,” the first problem that

arises is “Try to draw a square with sides of length --.” In other

words, the world of Suprematism where Malevich was eventually led was

the most rudimentary. In terms of information aesthetics, Suprematist

paintings were necessarily the paintings with the least amount of

information. In the end, are not the objectives of Malevich equivalent

to the delusions of Don Quixote?

In reality, the thing that was

most needed in this age was the return to a world of nothing, the

“non-objective world” in the words of Malevich himself, and the view

through the eyes of Malevich was equivalent to that of a revolutionary.

A new path was adopted after discarding all existing sense of value. At

virtually the same time, Le Corbusier discovered the white cube. The

awareness of these creators was linked by some deep undercurrent.

In the 1920s, Malevich worked on

the solidification of Suprematism, first creating a gypsum piece called

the “black square,” and then a solid carving called “Suprematist

Architecton” (Fig. II-10). The former could be said to be a single

building block, and the latter combined several rectangular solids and

was a relatively complex piece. Certainly, if enlarged, this could be

conceivable as an architectural structure as is.

In other words, after being led

to absolute zero, Malevich turned back with the intention of setting out

from zero. The impetus to simplify and reduce information stopped and

now turned to the gradual complexification and creation of information.

Therefore, the word “constructive” is appropriate. At the peak of the

Russian Revolution when there was no Czar and a completely new age was

beginning where everything needed to be built up from zero, Malevich

also started from the composition of primitive rectangular solids in the

same way as the establishment of society started from the creation of

the organization called the council (Soviet).

El Lissitzky, who drew paintings

under Chagall, received strong encouragement from and followed this

unique world of Malevich. The series of paintings entitled “Proun” (1920

to 1921) were all literally architectural paintings for a person who had

studied architecture. Although Malevich took the approach of adhering

to, in the words of computer graphics, a single orthogonal

three-dimensional coordinate system by principle and piling rectangular

solids, Lissitzky revealed diagonally arranged rectangular solids

through arbitrarily changing the coordinate system. The groups of forms

then folded and turned along walls and jumped from wall to wall,

stepping into the territory of space design (Fig. II-11).

“Proun” eventually focused on

architectural proposals that were realizable through cooperation with

the architect Mart Stam (1924). This a two- to three-story structure

with a C shape that floated high up in the air, and was securely

supported by two large shafts (Fig. II-12). A typical example of the “to

construct and build” preference of Russian Constructivism can be seen

here. In other words, first there were the column-shaped solids standing

straight up above the ground, which were also in the solid carving of

Malevich. The second was the cantilevered acrobatic structural element

with large arms projecting from the columns to form a shape floating

above the ground. In any case, it was an antithesis of the conventional

idea of being packed with walls

and stuck to the ground as the traditional brick structures show.

Lissitzky left Moscow to

interact with other artists and architects in various other parts of

Europe including Berlin, becoming a type of preacher of the Russian

Constructivist methods. The architects of Europe also focused on the new

trends in Russia, encouraging themselves to the development of

modernism.

The Russian Constructivist

architects had many optimists, who utilized a variety of new forms.

Malevich’s idea of Suprematism developed into the simple assembly of

glass cylinders and groups of large rectangular boxes of the Zuev

Workers’ Club in Moscow by Ilya Golosov, and Ivan Leonidov’s competition

entry for the Narkomtiazhprom building (Commissariat for Heavy Industry

in Moscow) in 1934 (Fig. II-13). The preference for cantilevers was

displayed in the volume of the audience seats of the Rusakov Workers’

Club of Konstantin Melnikov (1929) and the large projecting structure

for spectator stand of the Moscow International Stadium proposal by

Mikhail Korzhev (1925-26) (Fig. II-14).

The Russian Constructivist’s

preference for acrobatic structures was shown early in the famous

“Monument to the Third International” of Vladimir Tatlin (1920) (Fig.

II-15). This was a giant spiral-shaped skeleton structure with iron that

enveloped a slowly rotating main conference hall, and in this case the

structure was completely changed into a large mechanism. The roots of

the rotating landscape restaurant were also in Russian Constructivism,

and the architecture that was at work here was developed in essence.

The process of the departure of

Malevich from absolute zero, the move towards soaring column shapes, the

suspension of cantilevered arms, and the motion of architectural

elements as mechanical devices show that the architectural form of the

20th century was a system of forms that was learned in steps starting

from zero. The challenge of Russian Constructivism should certainly be

called the growth of a newborn baby.

(4) Revolution in drawing method

It was in Early Renaissance of

Italy where the perspective drawing method was born which represents

accurately the feeling of depth in structures and urban spaces. This

perspective drawing method was gradually improved over several hundred

years and was able to offer excellent reproduction of reality by the

19th century. Today, this has become a basic technique for designers

used for a variety of purposes, from pictures of expected buildings to

illustrations for simple pamphlets. However, the artists departed from

perspective drawings at the end of the 19th century and it became rather

modern that did not follow the perspective drawing method.

Because the Impressionist

painters drew vague impressions by discarding any realistic sense of

depth, the perspective drawing method, which aimed simply at accuracy,

became an obstacle. Futurism represented an abstraction of motion of

objects and Picasso merged multiple viewpoints into a single painting,

giving up on representing any of the order that is physically visible to

the eye. Such revolution in drawing method of paintings had no use to

the practical work of architects, though. Renderings of expected

buildings play the role to transmit accurately the information to the

owners of buildings, and so the vagueness and distortions of

Impressionism or congested angular images of Cubism merely confuse the

owners.

Therefore, the perspective

drawing method continued to exist among architects. However, the

revolution in modernist drawing methods that occurred among the artists

was not completely blocked out of the world of architecture. The

axonometric projections began to be widely used as an addition to the

perspective drawing method inherited from the Renaissance. The

perspective drawing has necessarily focal points on one hand, the

axonometric projection uses on the other hand an orthogonal coordinate

system of X, Y, and Z axes, and structures of a rectangular solid shape

are represented only by sets of parallel lines in the X, Y, and Z

directions.

The perspective drawing method

draws the scenery as seen when a single person is standing at a certain

location, and is therefore subjective. By comparison, axonometric

projections can be drawn without specifying where they are viewed from

and are said to be objective. For the people of the Renaissance, which

pursued the revival of humanity, the perspective drawing method was

appropriate, and if this was the case, then would not the age of

axonometric projections become an age of neglecting humanity? In any

case, it should be noted that the age of modernism that originated with

the glorification of humanity was in fact an age that discarded some

aspects of older idea of humanity.

One group that skillfully

employed axonometric projections was the “De Stijl”, Dutch

Constructivist group. The leader of this group, Theo van Doesburg,

designed the “Maison Particulière” (personal house) aiming at

axonometric projections in cooperation with the architect Cornelius van

Eesteren, and exhibited it at the De Stijl exhibition in Paris in 1923

(Fig. II-16). This picture has a plan view tilted at an angle of 45

degrees with height represented as additional. One sheet shows a birds’

eye view and another shows a view looking up from beneath the ground.

This is a viewpoint position similar to looking up at a scale model from

below, and is a viewpoint position that could not actually exist because

it would be viewed from within the ground.

The architectural theorist

Auguste Choisy drew similar axonometric projections from a viewpoint

under the ground in a theoretical architecture book in order to draw a

view looking up at the ceiling of a Gothic church

in the 19th century, and there could be an influence from this.

Perspective drawings have the weakness of making it difficult to

understand the assembly of a structure because columns and spaces are

represented as becoming thinner in the distance in order to express a

feeling of depth. Choisy drew this type of an outlandish axonometric

drawing in order to avoid these weaknesses. Doesburg employed such

features as a new method for recognizing space.

Furthermore, these axonometric

projections were employed by him as an important artistic expression. As

another axonometric projection of the project “Maison Particulière”, he

interpreted the walls and floors as combinations of plate-shaped

rectangular solids and reproduced these as a composition of abstract

shapes (Fig. II-17). Conventional European architecture mainly used

brick construction with stone surface or stucco coatings and had a box

shape surrounded by sturdy walls. These axonometric projections

disassembled this box shape, and interpreted structures as a set of

independent walls.

The painter Piet Mondrian of the same De Stijl group painted abstract

paintings by combining groups of rectangles on a two-dimensional plane,

and these Doesburg diagrams expanded them into three dimensions. He

presented this type of architectural image as an extension of an

artistic work. He was said to be a selfish person who had a habit of

using the person cooperating with him to crystallize his own ideas, and

then leaving him after quarreling. His collaboration with Eesteren was

also successful to choreograph splendidly and achieve a ground-breaking

expression.

De Stijl emphasized the

composition of multiple shapes even more than Malevich’s aspirations for

absolute zero degree, and this contributed to the establishment of a

compositional formation process. This was the beginning of the

self-disintegration of the cube practically that had been the starting

point of the 20th century creative world. But in fact, this was not

simply the destruction of the silhouette, but meant a change from the

centripetal thinking of Malevich to the centrifugal thinking, that is, a

preparation of creative tools to handle the more complex and diverse

requirements. The “Schröder House” (1924) designed by Rietveld remains

in Utrecht as the result, where rectangular surfaces painted in primary

colors freely intermingled with linear elements in a weightless space.

Instead of a symbolic and monumental single piece, this was a complex

shape that was to be the theme for the future.

In a time when independent

reinforced concrete walls were actually possible, this form was

immediately received as a new architectural form. The architect Mies van

der Rohe presented in successive proposals for a concrete rural

residence (1923) and a brick rural residence (1924) at around the same

time that were combination of independent plate-shaped brick and

concrete walls (Fig. II-18). Both of these were idealistic proposals

that were too far ahead of their time and did not come to reality.

However, this concept was realized in the German pavilion of the

Barcelona World Exposition in 1929, commonly known as the “Barcelona

Pavilion,” and became praised as a historical ground-breaking piece of

work.

Axonometric projections were

also employed around the same time by “Bauhaus,” an arts education

institution that made a large contribution to the pioneering of modern

art. This school, which came into existence in

The Art Nouveau style building

designed by Henry van de Velde was used as the Bauhaus school building

in Weimar, and Gropius remodeled a director’s room in this building,

which showed an epoch-making design method. At this time, Herbert Bayer,

who would become known as a graphic designer, drew the interior of the

director’s room using the isometric projection method, and this drawing

became well known (Fig. II-19). This is known as an isometric drawing,

where the left and right sides are tilted at equal angles of 30 degrees,

and the remaining 120 degrees form the corner of the front edge of the

solid. Although the isometric projection is included in the broader

meaning of the axonometric projection, in the axonometric projections

that are generally used, the corner of the end of a rectangular solid

forms an angle of 90 degrees. In Bayer’s isometric drawing, the angle of

the front end is 120 degrees, and the plan view is distorted.

Furthermore, when Bauhaus

relocated to

The axonometric projection is a

method of drawing that is not visually appealing, but is useful for

knowing the precise relationship between components as used also today

for assembly diagrams of axles of automobiles. Looking back from that,

the focus of building design can be said to have shifted to the assembly

of spaces, and this overshadowed the ideas up to the 19th century of

emphasizing the allure of external appearances, particularly facades,

and the details of this. Of course, this also contributed to the idea of

functionalism that emphasized the practicality of the interior spaces

instead of the absurd emphasis and pouring of capital into facades, and

certainly involved a variety of factors, not just the issue of drawing

methods. The extent of the contribution of the revolution in drawing

methods was especially so large that it cannot be overlooked. One can

say that there occurred a change in the early 20th century as large as

the appearance of the perspective drawing method in the Renaissance.

At this point, the idea of the

viewpoint seen by a human being was abandoned fundamentally, and a human

being as a subject became irrelevant for the objects. As the age of

Renaissance, although meant literally the revival of humanity,

emphasized in reality nurturing of selected individual genius, and as

spaces in the baroque age were ordered for a single person like the king

Louis XIV who said that “L'État,

c'est moi”,

humanity as meant in the Renaissance in wide meaning was a concept for

particular gifted men. The modern society that had shifted even further

from civil society to mass society was an age of the countless masses,

not of particular individuals. The axonometric projection is a method of

drawing that actually symbolically represents this modern age, and the

existence which bears an end of the architectural style of the 20th

century.

(5) Machine models

Machine, and particularly

automatic machine, must be raised as one of the new ideas that

characterized the early 20th century. As explained earlier how the

futurist artists had followed the road of machine cult, including

machine guns and tanks, the feature of machines as the symbol of the

20th century was automation. Although the futurists envisioned cities

assuming train and car transportation as horizontal movement devices and

elevators as vertical movement devices, the outlandish high-tension

power pylons that appeared in these paintings showed that the new age

was to be constructed by electromagnetism.

One aspect of the newness of the

neoclassical architecture from the 18th and the 19th century was that

the order created by beams and columns symbolically represented the

static order. Neoclassicism was modeled on the architecture of Greek

temples. For architects, the ancient Greek ornaments were important, but

the solidly standing columns and clear horizontal beams of the temple

architecture were furthermore important. This was a metaphor for

statics.

With the arrival of the 20th

century, metaphors for “dynamics” appeared in architectural designs. One

person who was particularly motivated by this word was the German

Expressionist architect Eric(h) Mendelsohn. He used the term “the

dynamics of blood” and sought a new architectural form as if pouring

cultural character to the science.

Although he is also known as the

designer of the “Einstein Tower” (1924) who also interacted with fellow

Jewish German Einstein, this celestial observatory standing on the top

of a hill near Potsdam was also intended to prove Einstein’s theory of

relativity from celestial observations (Fig. II-21). The tower that can

be seen as this multistory building actually has a smoke-stack shape,

and light passing through the telescope contained within the dome at the

apex can be reflected some times by mirrors and fed into a laboratory

stretching out horizontally toward the back. The curious structure like

kneaded clay with the windows gouged out by pallet obviously exceeds the

needs as a celestial observatory, and is certainly an Expressionist

design. Mendelsohn focused on this type motion inherent in the shape,

and made the term “dynamics of blood” his keyword of the design.

On the other hand, he presented

as the style of urban architecture a streamlined form with flowing

contour lines and continuous horizontal windows and dominated the time,

such as in the “Schocken Department Store” in Stuttgart and Chemnitz,

and the “Universum” movie theater compound building that was built in

Berlin’s principal avenue Ku’damm (Fig. II-22). Streamlining was chosen

as an architectural style that suits the urban background and had come

to take on a feeling of speed with street cars and automobile traffic.

Of course, since the buildings did not move and the streamlined forms

needed in transportation machines such as automobiles were not necessary

in real buildings, this was merely an architectural representation of a

metaphor for transportation machines.

Le Corbusier coined the phrase

that “a house is a machine for living in,” which had a significant

effect on the architectural image of the 20th century. This phrase has

become so famous that it is often misinterpreted. The misinterpretation

often arises from stretching the interpretation of Le Corbusier’s words

beyond the machine images considered by Le Corbusier into general

mechanisms. In order to understand an overall picture of the first half

of the 20th century, though, it is appropriate to take a broader

interpretation and inadvisable to focus strictly on the thoughts of Le

Corbusier.

The motif of the houses of Le

Corbusier was that of a luxury liner, with the machine being the ship as

a residential device floating in space. He presented also the

influential phrases titled “five points of modern architecture”. Those

contained the proposal for pilotis on ground level and rooftop garden,

and this was related to the image of housing designed by Le Corbusier

like a passenger ship brought onto land and supported by columns.

Although expressiveness of the kind of the metaphor of streamlining like

that of Mendelsohn was not Le Corbusier’s preference, he also created

words such as “Citroen House” as a play on words of the French car

Citroen. Furthermore, houses were given a style reminiscent of the

interior of a passenger ship, such as the introduction of steel spiral

staircases and multistory spaces.

What should be broadly

interpreted in the words “a house is a machine for living in,”

particularly with the appearance of low-cost residential apartments, is

the need to consider the arrangement of function within a unit,

particularly the three-dimensional reconstruction and striking

rationalization of the kitchen, which was the site of housework. At this

time, the idea of practical and Constructivist systematic

three-dimensional design was created, which was unrelated to the poetic

and romantic words of Le Corbusier.

The Constructivism of Russia and

the Netherlands, as described earlier, changed from the 19th century

perception of architectural beauty of focusing on the facade, and taught

that there was art in the assembly of cuboids. This Constructivist

aesthetics did not come from the architectural rationalism of necessity

and functionality that began to be led by Otto Wagner of Vienna and

others, but was created as an artistic movement. Because this eventually

found a building form in the

This diverse range of architects

conceived machines with their own images as models of the new

architectural style. In order for the buildings to become machines in

which people live, it was still early in Europe where most people still

lived in brick buildings, yet the various mechanical models had an

effect on the designs of each architect. The results were gathered

together in a large trend called functionalism. What functionalism has

given to the new house design was that the house functions well, that

is, it handles rationally the desired functions, and then houses have

been transformed into something like simple machines, even if they were

not highly complex machines.

As described earlier, the cube

was decomposed into planes by Constructivism and moved into the

dimension of compositional formation, and it moved into the dimension of

dynamic spatial formation through the subsequent addition of mechanical

models. The house itself does not move, it is the people that move. The

rational linking of people with architectural spaces became a device

that was useful to people. The theme of rationalization of the

circulation lines that were incorporated into the kitchen in particular

was symbolic.

In

The headquarter building was

formed from a high-rise tower and a low-rise building coiled around it,

and the building exhibited a complex shape that appeared to be the

result of rather functional considerations than the external appearance,

such as the arrangement of various rooms and circulation line planning.

The conference hall showed the acoustical calculations, and formed an

irregular dome shape. The visual presentation that integrates all parts

is, if anything, the staggered contour line as if enveloping the

complicated plan.

The abstract formation of

Russian and Dutch Constructivism, which composed solids while

maintaining a coordinate system of orthogonal X, Y, and Z axes,

transformed into the realistic functionalism with the grouping method of

picturesque sensibility during this period. Le Corbusier, surely the

poet of geometry, subdued the lakeside scenery wrapped in green in

addition to horizontally expanding the architectural volume. Meyer, on

the other hand, exposed the two unaligned high-rise towers and the

irregular dome, and frankly asserted functionality like a factory. Cubes

were completely dismantled and simple clear contours were lost.

Disregarding we love or hate, this can be said to show one aspect of

20th century reality of aiming for mechanical rationality, if we

consider that this was further developed into more highly mechanical

device image that became the architectural motif of the 1960s.

(*1) Antonio

Sant'Elia, “Manifesto dell'architettura futurista”, 1914.

(*2) Ibid.

4. Romanticism in the 1930s

(1) Temptation to fascism architecture

The 20th century began with the

pursuit of the simplicity of neoclassicism, sunk to the absolute zero of

the cube, then turned to the composition of cuboids and developed into

mechanical complexity. During these 20 years, 19th century concepts were

firmly swept away, and the basic form of 20th century architecture was

determined. This was the age of the creation of a new framework.

This age was the age under the

initiative of “reason” in the meaning of phlosophy, i.e., an age where

the rationalistic logic took precedence. The opening of this age had a

mere handful of avant-garde intellectuals. They rocked the foundations

on which the masses rested, and this would unfortunately be frankly

opposed by the naive public with an inclination to fear the change, even

if a new rational foundation would be built in the near future. The form

of the new architecture of modernism was often the subject of this kind

of disgust. The revolution by reason in the early 20th century did not

proceed smoothly.

In 1927, an experimental housing

exhibition was held by the German Worker Federation over the hill of

Weissenhof in the suburbs of Stuttgart. This incorporated the ideas of

the modernist architects from each country in Europe, and exhibited a

common architectural style that would later come to be known as

“International Style”, a particularly notable result even in the history

of modernism.

However, although this drew many

visitors, the question was also raised of whether future housing, where

the tiled pitched roof had disappeared and the walls were painted plain

pure white, would be accepted. A chasm appeared between the avant-garde

intellectuals who were proposing new forms and the common conservative

citizens.

The contours of houses were

thoroughly simplified, and rational formations based on Constructivism

became the overall foundation. Mies van der Rohe, who was also the

planner of the overall plan, exhibited an apartment block with a simple

long, thin box-shape that took away the artificialness. Gropius proposed

a steel framework house that would be the frontrunner of prefabricated

construction called in German “Trocken Montage Bau” (“dry assembly

building”). Le Corbusier realized housing that employed his own

architectural theory, which included pilotis, rooftop gardens, and

continuous windows. There remained indeed embers of individualistic

Expressionism in the vibrant use of colors of Bruno Taut’s advocating of

colorful architecture or the curved motif of Hans Scharoun, but the

architectural forms were significantly simplified and unified overall,

and this was a clear declaration of the birth of a new style based on

abstract cubes (Fig. II-24).

Incidentally, as the flipside to

this success of modernism, the year 1927, when the Weissenhof housing

exhibition was held, was actually a watershed moment in history. Unlike

The culture of rationalism and

universality of a civil society brought on once by the French Revolution

also flowed into late 18th-century Germany. Although even the people of

the city welcomed the cosmopolitan yet modern culture at that time, when

Napoleon eventually became an emperor who ruled over Europe, there was

rise of nationalism in various countries in the 1810s, and Napoleon was

overthrown. Gothic styles became the banner of nationalist symbolism as

resistance to the internationalized neoclassical styles introduced from

France. This rational universal architectural culture was wrapped in

dissatisfaction, and an approach of romanticism was revealed, which

attempted to preserve the native architectural cultures since the middle

ages that showed their own identity.

The rise of nationalistic

culture in the 1930s to the point of abnormality resembled this, and was

produced from the feeling of danger that traditional culture would be

rejected by a culture that strove for the new universality. These can be

said to have been romantic fluctuation in an age reason’s initiative.

Architectural style played a surprisingly large role at that time, and

the International Style and traditional style were now in opposition, in

the same way as the level of opposition between neoclassical and gothic

forms.

In the 1930s,

Amongst this, the young

conservative architect Albert Speer suddenly appeared on the scene.

Adolf Hitler, who tried to reproduce the authority of the Roman empire

under the name of the “Third Reich”, liked his architectural sense, and

this produced the architectural style of the Nazis that was based on

neoclassicism. Rationality and functionality that had been the themes of

modernism were repudiated from the roots up, and architectural styles

that were reminiscent of old Roman architecture and alters experienced a

revival. The theme was eternal buildings with a preference for simple

stone structures, and the futuristic and airy image of modernism was

intentionally discarded.

The Nuremburg rallying grounds

(1934) designed by Speer and the Berlin Olympic stadium (1936) by Werner

March were stone buildings that showed the approach of a preference for

robustness and a sense of weight that was in directly the opposite

direction from the skeletal lightweight structures of Gropius. This was

meant to be raised as the antithesis of modernism that started as a

torrent in the 20th century. Hitler, who had dreams of impossible

eternal structures, flowed with the blood of radical romanticism.

However, this was not simple

reactionism, but included a unique modernity. For the Nazis, who created

the Volkswagen, utilized the new media of radio for public

announcements, trampled Europe with blitzkriegs, and launched rocket

bombs at

In Italy at around the same

time, Giuseppe Terragni, Adalberto Libera, and the other members of

“Movimento Italiano per l'Architettura Razionale (MIAR)” created a

popular architectural style. Even here, although the rationality was the

key term for the architectural style, the focus was placed more on

visual effect of rationality, i.e., whether the appearance of

geometrical order was strictly regular and self-consistent, than on

functional rationality. The architectural style of the Italian Fascist

party was also born from these rationalist architects, which was due to

the aspiration for the order that tended toward the perfectionism of

shapes.

The geometric forms were applied

as an expression of the power of eccentricity. The features of fascist

architecture of huge cold walls, tall soaring pillars, and regular

sequences of architectural elements were derived from the

characteristics of simple clear shapes appearing threatening when scaled

up (Fig. II-26). Although the cubic shapes of modernism had brilliant

life breathed into them, these were also used for an monumentality

beyond ordinariness and aestheticism of formalism, and were largely

removed from the functional rationality for everyday life.

The monumental architectural

style of the Nazis and the Italian fascists had a common formal beauty

having a transcendental scale. In Germany, the norms recurred to the

classical age were sought, and in Italy, the proportional beauty of the

Renaissance buildings was sought. Both of these shared the motivation of

resisting the sudden flow of modernism.

The fact that Speer disliked

Gropius while feeling an affinity for Mies indicates that Speer felt

sympathy with the posture that Mies finally devoted himself to the

formal beauty of structural order rather than functional. Scientific

rationality discarded the irrationality of humanity as discussed

earlier, and the problem of the 1930s had a character of the hysterical

self-defense of this irrationality. Here can be seen the similar

composition as the romanticism of the early 19th century, that thorough

rationalism conversely nurtured a radical opposition.

(2) Budding point of organic architecture

The radical romanticism of the

1930s visible in Nazism became a blemish on history that carries the

confusion and destruction of society, but if we focus only on the

romantic fluctuation, there is an aspect that is the inevitability of

history. In other words, if modernism had walked independently without

accepting any criticism, then it would have become a new authority and a

healthy balance would have been lost.

The theme of the 1930s was that

the forward-looking reason and the opposition to it were the two forces

that were balanced to preserve the totality of humanity. A new movement

appeared in Northern Europe, in other words, the rural areas of Europe.

Alvar Aalto of

By the way, Japan also began to

be affected by modernism in the Taisho era, and coordination of

modernism and tradition became a large theme in the early Showa era,

that should also be treated as the same worldwide romanticism

phenomenon. Many people often questioned the “the Japanese” or

“Wafu”(Japanese way) in Japan, that is indeed the problems only within

Japan. But the theme of the harmony with indigenity and cultural

climate, that arose throughout the world as modernism became a torrent

in the 20th century and spread to every region, is best understood by

summarizing as the international romantic movements.

To oppose individuality against

universality of rationalism should be seen as an incidental reaction

process that was incorporated into the program of modernization itself.

At the least, the problem of “Wafu”(Japanese way) faced by the modernist

architects of Japan had the same entry point as the problem of cultural

climate faced by Aalto. Differences arise only in the construction of

the problem, if this is treated only as a domestic problem or as

elevated to a problem of universal style.

If we look at what Aalto did, he

first absorbed the International Style where the concept of the cube was

subtly developed, and then melded with the environment of this style. In

the Paimio Sanatorium (1929), Aalto took the rational architectural

style of steel reinforced concrete that had already been developed by

the pioneers in

There was already no shadow of

19th century architecture, as if Aalto was a person from a generation

that did not know of 19th century things. Aalto again used neoclassical

design methods up until just prior to Paimio, and used sunken Doric

order columns in a 1924 Workers’ Club (Jyväskylä). This corresponded to

the neoclassicism of Behrens at the early 20th century, and was not the

neoclassicism of the 19th century, though. This point was equal to the

simplified neoclassical style exhibited by Asplund in the Stockholm

Library (1920 to 1928), with Northern Europe showing a time lag of

approximately 10 years compared with the rapidly changing styles of

One feature of Paimio that

attracts attention is the minimization of connecting circulation lines

between buildings with a folded line arrangement like branches

bifurcating while growing (Fig. II-28). Because the rationalism of

Constructivism employed a framework of orthogonal X, Y, and Z

coordinates, it did not give bends other than 90 degrees, and Aalto was

suitable for the meaning of functional rationality. In other words, the

arrangement that appears to be free at first glance in Aalto’s building

composition was a more natural expression than functionalism.

Although Hannes Meyer exhibited

radical functionalism in a combination of towers and horizontally

expansive headquarter building with a large swollen conference hall in

the competition entry for the Palace of the League of Nations, Aalto

took the same compositional method and removed the orthogonal

three-dimensional coordinate system, shifting to a topological system.

Both of these took the background of a composition method with the

actual picturesque style composition as used frequently in the 19th

century, i.e., combination of towers, masses, and horizontal elements,

which is so similar to the trinity idea of “shin”(formal),

“gyou”(semiformal) and “sou”(informal) in Japanese flower arrangement.

The idea of scenic design that preferred this kind of change and motion

was merged with functional rationalism. For Aalto, functionalism sat on

a more relaxed, natural functionalism, and this later came to be

referred to as organicism.

In order to understand this

organicism, there is one pattern motif; it is the horseshoe shape that

can be seen at the entrance to Paimio. This was the approach leading up

to the deep entrance that allowed canopies to be attached to the sides,

and showed the merest hint of naive functional rationality. This calmly

flowing horseshoe shape could also be seen in the Garkau farm house

(1922 to 1926) of Hugo Häring, one of modernist architects group in

Berlin, who criticized the geometrical system of “A Contemporary City

for 3 Million Inhabitants” proposal of Le Corbusier and raised its

problem with the orthogonal three-dimensional coordinate system. There

was a cattle barn and the owner should give feed to the cattle, that

resulted in a single horseshoe shape instead of a straight approach and

return (Fig. II-29). The second story of this cattle barn had a concrete

floor slightly tilted like a cone, which was to make it easier to drop

hay into the feed troughs below. This barn with the distortions is

perhaps better said to be a cattle breeding machine rather than a

building, but was an organicist machine unlike the mechanical images of

the Futurists and Le Corbusier. Häring who was known as a theorist also

advocated for the term “organic” architecture.

It is famous that the horseshoe

shape was used in the large residential apartment block of the Siedlung

Britz in Berlin by the Expressionist Bruno Taut, where it was not a

functional form but a mere symbolic form. The horseshoe shape of Aalto

was closer to the functionalism of Häring. It is unknown whether Aalto

viewed the plans of the complex of the Garkau farm houses, but there

could be found a group of different forms of buildings including a

pointed arch-shaped structure and so on, with the arrangement also

seemingly random at the first glance. The site plan of Paimio certainly

set a conceptual precedent there.

Eventually, the characteristic

organic curves called Aalto curves appeared in the 1930s, such as in the

meandering ceiling of “Viipuri Library” (1935) and the flowing slanting

walls of the “Finnish Pavilion at the New York World Fair” (1939) (Fig.

II-30). These were the theme through Aalto’s lifetime, and appear in

walls and ceilings in a variety of buildings. Traces of the rational

thinking of functionalism could be not seen here any more, and were pure

intuition that exceeded rationality. The transition from the horseshoe

shape to Aalto curves can be thought of as jumping from rationalism to

irrationalism. However, Aalto curves differed from the intuition of

Expressionist architecture, such as the Einstein Tower or the Second

Goetheanum by Rudolf Steiner, and are undoubtedly the result of a

transition from functional rationality to organicism.

The greatest harvest of

romanticism in the 1930s was Aalto. This certainly continued the

development from 1920s Constructivism to functionalism, and yet it

included a critical look at modern rationalism. The orthogonal

three-dimensional coordinate forms were discarded and the mechanical

coldness of radical functionalism was also discarded, but this did not

suffer from the syndrome of hysterical reaction against modernism of the

Nazi and fascist architectures. Modern rationalism could relax in the

forests of Northern Europe on the margins of Europe while observing the

battle between modernism and anti-modernism in the center of

As can also be seen from

Futurism and Constructivism, modern rationality was tightly bound to a

revolution against the existing senses of values. The rationalists of

the 1920s wiped away the things of the 19th century and aimed at

building up a new value system. Reason had to be clear and simple, and a

banner for the revolution had to be summarized into a single word. Many

people cannot be appealed to and led in a single direction by a vague

and complex image. Modern rationality therefore aimed for the direction

of forming a one-dimensional sense of value. The white cube of Le

Corbusier visually symbolized this one dimensionality. Aalto curves

appeared as a visual symbol with a sense of value that repudiated this

white cube.

Aalto curves are a form that

surpasses rationality, and have unlimited development and freedom that

appears merely as playfulness at a glance. This also represented the

formality of neoclassicism of the early 19th century as well as that of

the freedom of romanticism, and the composition of the contrast between

the aspiration for formality of modern rationalism and the trend towards

freedom of organicism was revealed at this point as if in a faceoff.

Romanticism only has a relative existence within the structure of ideas

of modernism and only takes the position of being able to savor the

freedom of the heart thanks to the existence of rationalism that

preserves formality. Freedom that forgets formality is nothing more than

simple chaos, and cannot form a functional structure.

5. Theory of the spatial structure

(1) Way of thinking in cultural anthropology

The composition of antagonism

between modernism and fascism of the 1930s, i.e., the antagonism between

20th century rationalism and radical romanticism, is lost in the period

of chaos of World War II.

This was also the same in

Whereas nationalism became a

relic of the past and advocacy of excessive nationalistic identities

were considered dangerous. Internationalism was strongly pushed forward,

particularly in the socialist bloc, and a social order surpassing

nationalism and religion was constructed. However, because this new

social order took on a form of being pushed by brute force, the

subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union was accompanied by a reactionary

resurgence of old religions, and these became wrapped up in fierce

interracial conflicts.

Although the structure of this

victory of functional rationalism and defeat of nationalistic

romanticism was the solution to the problems of the 1930s, the times

pass rapidly and the doctrine of duality was quickly overshadowed.

Functional rationalism was blamed to be too simple and a more skillful

logic was searched. Whereas, apart from the 19th century global system

of nation states based on nationality and history, people’s eyes were

opened to the existence of more real social groupings, and the cultural

anthropology began to spread. The ideal shape of cities and buildings

did not simply follow scientific rationality, and was searched in the

different point from global power structures or governmental

administration systems.

The term “structure” became

convenient there among architects and urban planners. This was not the

physical structure referred to by structural mechanics, but was more a

soft meaning of social structure or cultural structure. In France, the

cultural anthropologist Lévi-Strauss performed research on primitive

people, and the existence of primitive social structures was treated not

simply as the mechanisms of slow-developing societies, but as knowledge

of social construction applied universally to all mankind (*2). This

formed a school of thought called “structuralism,” and had an effect on

a wide range of fields. The logic of primitive societies was even

applied to the analysis of large cities in developed countries, and this

was accepted as a new theory by architects and urban planners.

The writer Bernard Rudofsky

wrote the best-selling book “Architecture Without Architects (*3)” in

1964, and presented settlements of primitive societies, noting that

designs that did not exist in any kind of modern architectural design,

or that surpassed these, were realized by unnamed people (Fig. II-31).

Although this itself had a direct connection with cultural anthropology

of structuralism, the discussed themes were the same.

The two dimensional antagonism

between rationalism and irrationalism in the 1930s focused on small

tribes instead of nations, and was skillfully replaced by a third method

by focusing on logic that only prevailed in small groups rather than

globally universal logic. Way of thinking from the part rather than the

whole made it as possible. Although the theme of cultural climate

pursued by Aalto and others around the 1930s were only rated as having a

peripheral relationship with the center or complimentary to global

universal logic, at this time, the concept of a universal whole was

rejected, and a new awareness was born that the universality already

resides at the periphery of the world.

French structuralism developed

into the semiotics of Roland Barthes and others, giving birth to

architectural theory that employed semiotics, and this vocabulary also

had a large effect on architectural criticism. However, it was not

argued yet on the way of thinking of structuralism inherent in the

architectural thought of this period. In particular, the way of thinking

that was common to the cultural anthropology of structuralism is

somewhat useful in order to understand the path traced by the

architectural styles of the 20th century under the initiative of reason

(*4).

The

Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck

undertook studies of the Pueblo Indians and other people, and recognized

that village structure that was also called primitive had a unique

spatial sense of value. He then applied this theory to the design of an

“Orphanage” (1957 to 1960) in

The house in a primitive village

was first created without division into functional partitions and

without thinking about how it would be used. For example, if there was a

village with a certain number of families, then only that number of

houses was created, and these were arranged to form a suitable circle

around a central space that was shared. As the village gradually

developed, with the creation of warehouses and temple-like spaces, they

were often shaped like a house. In other words, unlike the idea of the

division of roles of functionalism, the form of buildings and the

village structure that determines their distribution are decided at

first. The empirical knowledge about the relationship between parts and

the whole is useful there.

In the case of Van Eyck’s

orphanage, two types of large and small cubic space units crowned by

each dome roof are created, and then integrated appropriately with the

administration building and front garden space to the whole complex

(Fig. II-32). This was certainly the application of the village

structure of a primitive society to architectural plans. It was not only

this work, but he applied what should be called a design method of

“structural theory”. In the proposal for a new church under the concept

called the “wheels of heaven” (1964), four circular rooms produced the

shape of ladder-shaped frameworks, and this was also a development of

this method(Fig. II-33).

What is necessary for the

structural theory method, is to define the puristic base forms as the

units and then the connective relationship between the multiple units as

the structure. In the functionalist method, the whole was divided into

several functions, and the space was partitioned according those

functions, whose method is named zoning. This had the feature of the

method of partitioning, where the parts were created only after the

whole is partitioned and the parts could not be independent. In the

structural theory method, the parts come first and the whole is decided

later. There the parts could be even independent separately according to

circumstances. As it is named the system theory to inquire how the

relationship between the parts and the whole, the nature of the system

differs here between the two.

The changes in 20th century

architectural styles were actually produced from such changes in the

nature of the system. Constructivism took the formal system of geometry

as the theme, functionalism used this as a base to take spatial system

as the theme while considering the function of the space, and organicism

took more natural spatial system as the theme by discarding the themes

of formal system. Structural theory then attempted to give definite

patterns to spatial system that are irregular at first glance and

proposed patterned spatial structures.

The focus on primitive society

came against a background of a large historical movement of the 20th

century of self-denial of European society. Rudofsky certainly admired

the organic spatial structures established in the primitive society that

are not necessarily designed by anyone. This means a critical view of

the European civilization where is created the habit of singling out the

artist by their personal name since Renaissance.

At the same time, this was also

against the background of the profound impulse towards universality

aimed for by 20th century Europe, and was not carried out under any

simple attempt to protect primitive society as humanism. They entered

primitive societies, performed structural analysis, and deduced abstract

logic. For the architects, this logic was brought back and applied as

new design methods. Even when a model was sought of primitive society,

this was a field for sophisticated development by modern rationality.

Incidentally, also in Japan,

many surveys of the historical town at various sites in Japan were

conducted in the 1960s under the name “design survey” by architects and

architectural historians like Yuichiro Kojiro, Mayumi Miyawaki, and

others, and research on Japanese unique spatial structures was conducted

resulting into the book “Japanese Urban Space” (*5) by Arata Isozaki and

others. Broadly speaking, this can be said to be one corner of the

global age of structural theory. Attempts to elucidate the principles of

spatial structure from primitive villages continued in Japan up to the

world village survey of Hiroshi Hara (*6).

Until now, the structural

outline of the International Style and its regional development has been

widely used to understand the architecture up until the 1960s. However,

as noted earlier, this dualism was just a theme of the 1930s, and the

initiative of 20th century reason did not necessarily stop at that

point. It should be noted that the insufficiencies of the logic of

functionalism were once surmounted by the logic of the structural

theory.

(2) Urban structure

The Estonian-born American

architect Louis Kahn was known for unique mysterious forms, and he came

to be like a guru amongst architects. However, this was a result of his

personal sense of form and psyche, and has almost no relation to the

underflows of history of the 20th century. Although it is scarcely

pointed out, his logic relied certainly on the spatial structural theory

of this period. This provides a glimpse of the footsteps of 20th century

reason.

He presented proposed reforms to

the city center of

Only that, each of these units

was completely different from the image of high-rise buildings that had

been born with the gradual development of theories of rational and

economic structures. This idea also differed fundamentally from the

architectural styles of the time that continued to transform into

asymmetric complex shapes that considered the functional spatial

partitioning, and carried a monumentality like classical altars. This

came to solidify the symbol of Kahn as a hero who rejected 20th century

modern rationalism and pioneered a new monumentality. Furthermore, the

theory that 1970s post modernism started from that time has also been

claimed. Looking at history from a bird’s eye view, however, the way of

thinking of Kahn is located within the genealogy of modern reason.

Kahn was also famous for his

clear separation of “served spaces” and “servant spaces.” His theory was

that it would be good to have main spaces where the function is not

particularly defined and support spaces supporting them behind, and this

was again a method peculiar Kahn that supplanted functionalism. For

example, at the Pennsylvania State University Medical Research Center

(1957 to 1964), a column-free space with a square floor plan was

prepared at first, and stacked into seven stories solids, whose five

towers as main units are combined via a central tower as a forum. The

thin square towers as the support spaces that contained the toilets,

elevators, etc. are added outside of the each main units. The structure

of individual, large square main spaces with small square support

spaces, and the structure of a grouping of those five units clearly show

the relationship between the parts and the whole in the structural

theory (Fig. II-35).

The structural theory of design

also had a large impact on Japan, and Kenzo Tange took this as his own.

In the Yamanashi Culture Hall (1964 to 1967), several cylindrical shapes

were lined up and office spaces etc. are arranged appropriately in

between (Fig. II-36). At the least, in the floor plan, this created the

feeling of cone-shaped residences in a primitive village arranged in a

line, but in this case, they were cylindrical columns that contained

toilets and stairs. These were servant spaces in the words of Kahn, and

at the same time columns that formed a framework, and therefore they

were arranged in an orderly uniform lattice rather than in a free

arrangement, which support the rest free space as served space.

Van Eyck designs that were

similar to it at a glance in a roman catholic church (1968) in The

Hague, where the circular shapes were small prayer rooms, and the pipes

of sky-lights opened in the ceiling (Fig. II-37). For him, the circular

unit was an independent spatial unit, and this itself was

self-promoting. It seems after all that Tange referenced each of the