> BACK

revised on 2010.10.16

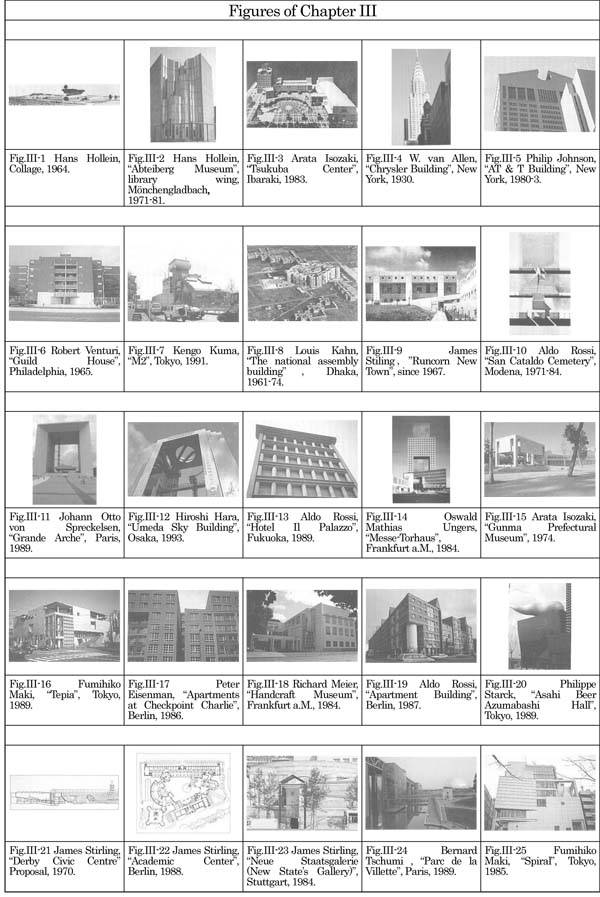

III. Reorientation

6. Post-modernism

(1) The

resurgence of sensibility and mannerist hedonism

The movement to reject modern rationalism started in

Mass society, which was a theme of the 20th century, was based on

the principle of sharing with everyone, and arrived at the view point

that science and functional rationality were the foundation of

everything. However this held nothing more than aesthetics that embodied

vast yet shallow values like pop art, which is easily understandable for

everybody. The meaning of Pichler’s words was that in order to find

depth in aesthetics, we should avoid situations like a mobocracy and

rely on the talents of a few. If we take his words at face value then

they mean that we should discard modernism and return to the Renaissance

in the early modern ages. The House of Medici in

On the other hand, Hollein said,

“A building is itself. Architecture is

purposeless (*2).”

He posited that architecture must have an absoluteness that does

not conform to anything. Architecture also does not play a subordinate

role like serving some kind of purpose. The theory of usefulness and

appropriateness to a purpose that began to be supported by Otto Wagner

at the turn of the century in Vienna began to be overturned in this very

Vienna. Furthermore, the systematic thinking of purpose-rationality that

should have been organized in the functionalism of the 1920s was

discarded.

During the move toward functionalism and structural theory,

architecture was in the position of being analyzed, theorized, and

reformulated as a servant of man. With the relationship between purpose

and means always in mind, Hollein released architecture from the

shackles of this kind of purpose-rationality and attempted to return to

an absolute viewpoint. This meant completely ignoring the process of

trial and error of modern rationalism.

If this was the case, how would architecture evolve? The left

brain alone, which is responsible for intellectual judgment, cannot

produce thoughts. The idea that architecture would follow the instincts

of itself was that the architect would create by following his

intuition. However, of course, buildings were not to be formed only on

the basis of visions drawn from the right brain. What he had advocated

was the unlocking of sensibility that had been suppressed by reason,

where reason was made subordinate to sensibility.

In 1964, Hollein drew a shocking collage that features a large

aircraft carrier placed against a gently undulating idyllic background

(Fig. III-1). Depending on one’s point of view, this could be seen as a

variation of the

“

Of course, a battleship in this location would be unable to

execute any of its original purposes. This surrealistic image of

Hollein’s surpassed the logic of purpose-rationality and the aircraft

carrier was self-sustaining as an independent entity. In other words,

architecture as a high-level technique was not buried under a slew of

purposes as per structural theory but was considered as fulfilling its

own vitality.

Hollein designed the library building in the Museum Abteiberg

(1972-1981) with one corner of a square prism melted by solvent (Fig.

III-2). This square prism, which was coated with mirror glass and

appeared only as a grid outwardly, surely symbolized the cubic

systematic rationality of the early half of the 20th century, while the

melted area symbolized artistic intuition that completely ignored

artificial systems. This also represented the phenomenon of competition

between and the dissolution of two value systems, which can also be seen

in

“The Urban Mark”

by Peter Cook. Thus, the autocracy of reason was already being

undermined. Even so, systematic rationality could not be completely

ejected from architecture, and there could only be proposed a

continuation of the dualistic competition between formal order and free

amorphism.

Although the architectural forms at the early 20th century

exhibited a variety of trends, the geometrical silhouettes and white

coatings that were aggregated in the International Style were

precipitated as common items. There was a trend of compressing

information, which was nothing but the work of the reason. With the rise

of post-modernism, the sensibility began to create artistic

possibilities, and having a lot of information was seen as good on the

contrary. Therefore, diverse colors and raw materials became acceptable,

and there was also no need to follow precise geometry.

In the colorful interior of the Museum Abteiberg, where there are

bright white walls flooded with light, there are also walls dark like a

cellar’s that are inlayed with erotic reds and blacks. The walls also

feature a mixture of various shape elements, from geometrical forms such

as rectangular volumes and grids to the amorphous shapes of a saw-roof

and twisting retaining walls. All possibility of expression were

attempted and one-dimensional rigidity was intentionally avoided.

Critical composition that the systematic rationality was

destroyed and the free sensibility were fomented, was an essential

mechanism for prompting the shift to post-modernism.

“Critical”

implies both

“urgency”

and

“to critique and to review,”

and attempts were made to exaggerate and express this urgency. This did

not result in a period of naïve sensibility but somehow destroyed the

initiative of reason and prompted a move to the initiative of

sensibility.

Back in the late renaissance period, that is, the period of

mannerism, there were architects who stood on this kind of borderline.

One was Giulio Romano, who was active in

From Italian word

“maniera,”

which means

“manner,”

the word

“Mannerism

(Manierismo)” was

coined. Compared to the ages of the brain,

this was the age of the hands. In other words, there was a change from a

period of ideas to a period of sensibility that were free from reason.

The high renaissance was a period of idealism, that is, popular ideas

such as the ideal of the divine proportions of human body. This was a

period marked by the perfect order that was virtually imprinted on the

brain of people, and then the passion for idealism eventually cooled and

people began to demand the restoration of humanistic things. The hands

began to act freely in order to get away from the dominance of reason.

Arata Isozaki criticized the initiative of the reason at the

early half of the 20th century and plotted its demise by borrowing the

methods of mannerism. He studied the works of the surrealist Marcel

Duchamp and intentionally broke functional rationality and systematic

completeness such as by embedding doors that did not open, designing

seat backs based on the curves of Marilyn Monroe, and presenting

incomplete structural images cutting off abruptly the beams that should

be extend further. This was very similar to the irony of Giulio Romano.

The Tsukuba Center Building (1983) designed by Isozaki

incorporated motifs of the Piazza del Campidoglio of Michelangelo and

the columns of C. N. Ledoux, which exhibited the method of

“quotation”

intentionally destroying the myth of originality, and it satirized the

myth of completeness with a design that appeared as if part of the

building had been destroyed (Fig. III-3). For a naïve, ordinary person

who carries around a common image of the completeness of a building,

this broken building and the parrying design is incomprehensible, and

they want to blame the architect for betrayal. However, this type of

mannerism was actually attempted in Japanese “Sukiya” style of

architecture in 16th and 17th centuries, that is, the tea houses design

which enjoyed intentionally parrying the architectural rules and myths

of the high-quality.

Mannerism is an intellectual game, and the

raison d'être

for its existence is to break the perfect

order of reason. Although this was a critique against the initiative of

reason, it differed from the romanticism of the 1930s in that it did not

aim to completely resolve and discard reason. It was sufficient to free

the right brain that had been suppressed and to release one’s

sensibility. To establish the communication based on sensibility between

the creator and the viewer visualizing the falling down of a rational

object formed the art. The intention of Hollein who created an object as

if a pure geometric prism was melting down was also the same.

(2) The

semantics of the consumer society

Although modernism departed in search of new forms and spaces

suitable for the mass society of the 20th century and initially

exhibited a trend toward utopian socialism that sought the reawakening

of free exchange between people, the capitalist economic system

immediately commoditized the structures of modernism. In the America of

the 1920s where it can be said that brute economic force was emphasized

as the reason for living even more than artistic will, the motifs of the

form of modernism were borrowed for the decorations of skyscrapers (Fig.

III-4). Passionate artistic intentions were chopped up and fragmented by

unemotional economics. There is also another aspect in that, thanks to

this, the motifs of the form of modernism dotted the scenery of the city

and were therefore actually able to be seen by the public. Thus, while

capitalism was giving birth to millionaires on the one hand, on the

other it was promoting an age of popular art of mass society.

The patrons of architects of the 20th century were no longer

kings and nobles. In the 19th century, the patrons were joined by

industrial capitalists and in the 20th century they were joined by the

communal rights of mass society. Although in the East Bloc the socialist

governments formed only from the public become the new patrons, in the

West the invisible faceless mob of the countless masses of consumers

became the new patrons. In any case, an architectural culture wherein

the social system itself became the patron was established, and the

architectural styles also reflected this characteristic.

In the 1970s, an American architect Philip Johnson suddenly

revived post-modern historicism who was once mentored by Mies. Among the

skyscrapers in New York where the style of modernism had become standard

starting with the Seagram Building by Mies, he introduced the AT&T

high-rise building with a Romanesque entrance hall and a crown of a

Chippendale chair decoration (Fig. III-5). In addition, high-rise

buildings in a variety of historicist styles were created one after

another, such as high-rise buildings crowned with minarets with a

gothic-style motif and coated with mirrored glass. Although much of

intellectual followers of modernism frowned at his betrayal, the general

public applauded the high-rise buildings that became landmarks of the

urban landscape and were not merely square boxes. Johnson departed from

the ascetic design ethics of Mies and insisted on reviving the

pleasurable aspects that was originally inherence in architecture.

However, reviving historicism meant only focusing on a small

aspect of the aesthetics of architecture. Because the original nature of

post-modernism was to revitalize all possibilities of architectural

beauty that had been suppressed by reason, the post-modernism of Johnson

was only one of many styles. In particular, the historicist styles of

post-modernism in the United States of America were notably remarkable

compared to Europe, and this can be understood as America, having only a

brief history, might have had an inferiority complex against the

historical styles of Europe.

Michael Graves also

attempted to modernize historicism in the same way by using classical

styles as a motif using vibrant colors, and it could be said that he was

attempting to modernize the decorative architecture of the Art Deco

style. This direction of polychromy was also the antithesis of the

International Style that exhibited abstemious forms in the neutral

colors of white and black. The tendency toward classicism meant to

revive the formalism of, for example, columns arranged and displayed

regularly, and also to discard the successes of functionalism.

Johnson’s style emphasized sometimes the appearance of gothic

forms modified by Expressionism even more than 19th century historicism

and had the will to restore everything relating to the pleasure of

shape. The fact that the revival of Art Deco occurred alongside

post-modernism demonstrates the trend toward the commodification of

artistic shapes in post-modernism. This commodification was not merely

the simple desire for imitations sold at a store but was related to the

deeper principles of the system of capitalism.

Karl Marx had already shown that capitalism itself was based on

simple and clear principles and was a clever system for recreating the

value in the relationship between products and money, and Baudrillard

focused on the fact that the economic system of capitalism created a gap

between the true value of a product and its symbolic value, and he

explained the start of the spontaneous movement of symbols or signs

alone (*3). Artistic works give rise to imitations, and the world of

simulations called

“simulacra”

is created by the process of simulation.

The set of objects left by the first wave of historicism within

post-modernism can be understood using this concept of simulacra. The

Chippendale-style form as used by Johnson in the high-rise building did

not necessarily have logical consistency. Even in the gothic style,

although there was certainly an expression of the perpendicular intent,

the gothic styles of the Middle Ages bear absolutely no relation to the

structure of modern high-rise buildings. This kind of image that uses

historical forms was created in another dimension, and this image was

not only preferred by Johnson but it was also desired by the general

public. The image was separated from reality to create an isolated world

within the common vision of the public.

Through his book

“Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture,”

(*4) Robert Venturi argued against the academic thesis of modernism that

architectural designs must have a uniform systemization, and in

“Learning from Las Vegas,”

(*5) he positively approved of the raison d'etre of huge billboards and

placed value on the representational aspect even more than on the

architectural body itself. That meant that the items that had captured

vulgar interest were understood as the reality of simulacra in a

capitalist society and then the genre called

“pop architecture”became

independent (Fig. III-6).

On the one hand, the independence and consistency of architecture

and the ethics to preserve these were completed based on the necessity

theory of modernism starting at the end of the 19th century. On the

other hand, there is the principle of capitalism that functions on the

principle of increasing money. And there is a tug-of-war between the two

extremes. Post modernism proceeded to follow a path of giving priority

to the latter, dissecting architecture into pieces and transforming it

into an aggregation of simulacra. The billboard architectural style of

Venturi and the figurine architectural style of Johnson have developed

the vulgar interests of capitalism into a firm architectural art genre.

As its extension, architecture as a set of simulacra was realized, which

is a mixture of a classical column, ruins, and hi-tech style as in

“M2”

by Kengo Kuma (Fig. III-7).

The modernism that idealized the architectural image as a

one-dimensional rational system starting from a cube stood helpless

facing the condition of the individual parts being fragments of

scattered simulacra. The fact that consistency in architectural design

was merely one ideology became known at this time. However, this was

certainly considered to be necessary for starting a new age in the early

half of the 20th century, and this was a time when ideology was useful.

After the problems significant for the human history in the early half

of the 20th century had already been resolved, the usefulness of

ideology in society was lost. The difference between Mies and Johnson

was the symbolization of this changing of the times.

What modernist architects aimed for was that mass society, in

other words, even those with the lowest levels of income, enjoy the

architectural qualities, as is seen in the proposals of the Siedlung and

existence-minimum housing. This was a global theme of the 20th century,

from socialism to social democracy that surpassed the conflict between

the East and West Blocs. Even the mass of people became soon no longer

find their ideals in the ordered space created by the communal apartment

blocks and those housing estates. People began to prefer private

ownership of

“differentiated”

houses with some kind of decoration, no matter how minimal, and

advocated individualism over communalism. The age was dominated no more

by the socialist utopia of the early 20th century but by the

pseudo-utopia of capitalism where the simulacra flitted about.

The thing that monolithic socialism could not withstand is best

described as the political forms of the post-modern phenomenon.

Socialism called for the abolition of classes and attempted to

reconstruct society based on one scientific principle in order to remove

all of the historical and traditional evil practices. Society was

re-started from zero, everything was decided by reason, and a consistent

public system was constructed. This was symbolized by the system of

geometrical shapes that Russian Constructivism attempted to build.

While fractures appeared in the system constructed by reason, the

architectural image was dissolved by the change to an aggregate of

autonomous parts and finally became a mixture of pluralist values. In

the same way as that, in the 1980s, the system of socialism also

suddenly collapsed due to the actions of the young people acting freely

guided by their own sensibility. This must not be seen as merely a

simple collapse but as representing a process of reorientation from the

initiative of reason to that of sensibility of the tide of the 20th

century.

(*1) Walter

Pichler, Hans Hollein, ‘Absolute architecture’(1962),

in: Urlich Conrads (ed.), “Programs

and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture”, English translation: Lund

Humphries, Londn & MIT, Cambridge, 1970, p.181.

(*2) Ibid,

p.182.

(*3)

Jean Baudrillard, "Le Système des objets", 1968 (Japanese translation by

Akira Unami, Hosei Univesity Publishing, 1980).

(*4)

Robert Venturi, "Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture", The

Museum of Modern Art Press, New York 1966. (Japanese translation by

Kobun Itoh,

Kajima Shuppankai, Tokyo, 1982).

(*5)

Robert Venturi, "Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture", MIT

Press, Cambridge MA, 1972, (Japanese translation by Kobun Itoh,

Kajima Shuppankai, Tokyo, 1978).

7. Typological

classicism

(1) Cubic

typology

The fortress of unitary dominance of modern rationalism was

attacked from various directions. Concerning the idea of the absolute

architecture of Hollein et al. there emerged another kind of absolute

architecture. While Hollein followed a direction of dissolving form,

there was a reverse way to liberate humans from the yoke of modern

rationalism through strengthening formalism that made form even more

firm.

Louis Kahn created a unique world with a mysterious sense of form

using simple geometric shapes while at the same time searching for the

logic of spatial structure theory. In the Dhaka capital plan that he

started in 1962, this was given a large-scale form (Fig. III-8). The

national assembly building had an strong order with central plan

integrating simple shapes such as squares, circles, semicircles,

octagons, and triangles. Although these simple solid shapes, plain wall

surfaces and openings are missing detailed functional considerations and

the structure does not appear very comfortable, it is unparalleled

concerning monumentality as a national assembly building.

In the meaning of absoluteness that exceeds function, another

kind of absolute structure is displayed here in the form of bloated

formalism. This was the aesthetics of transcendence expressed in altars

and temple buildings such as ziggurats and pyramids in a period when

society was dominated by ancient myths. It was, as it were, the

rejuvenation of the ancient in a modern society. The parliament is

believed to be a place of openness and transparency in a democracy and

there was a trend to design parliament buildings without too much

dignity. Thus, Kahn’s method represented a revival of ancient mysticism

that modernism should have completely discarded.

As the systems of modern rationalism become more complete, the

designs of Kahn that transcended this were viewed as heroic.

Architectural theory which is believed to have started with Vitruvius in

ancient Rome was divided under the establishment of the modern teaching

system into architectural science as a scientific system on the one

hand, and an essay on architecture as the poetic and philosophy of

poiesis on the other hand. And the design style of Kahn was indeed the

one that rejected scientific architecture and simply embodied essay on

architectural as the poetic philosophy of geometry. The spatial

structure theory that stood on the an

extension of modern reason was also transformed into something poetic by

his words.

Although James Stirling from England presented a unique

intellectual design method starting from the functional rationalism in

the 1960s, like the faculty of engineering of Leicester University, the

history faculty library at Cambridge University, and the Queen’s College

in Oxford, he turned in the 1970s to formalism which arranges

geometrical units. In Runcorn New Town (since 1967), a simple structural

form can be seen of a structure with a horizontal volume running on

space supported by pillars that appear to have been inspired by the

colonnades of fascist architecture (Fig. III-9).

Architects Kahn and Stirling who followed completely different

systems formed a single movement based on this point of aspiring to form

that transcends function. This was converging on another kind of

rationalism of the

“typology.”

This rationalism was distinguished from the scientific spirit build by

the modern reason, and paradoxically to be said irrational rationalism

in some ways.

The

“typology”

of the 1970s mentioned here turned the future-aspiring psyche of

modernism on its head and was born from the idea of reconstructing the

log of architecture by returning to its point of origin. During this, in

the middle of the 18th century, Laugier reevaluated the theory of

primitive huts mentioned in the

“Essai sur l’architecture,”

and the interest on the neoclassicism of Ledoux and Boullee during the

French Revolution grew significantly. The essence of neoclassicism,

known as

“typology”based

on the return to the primitive and simple geometry, was reconstructed as

a 20th century theory. This theory was carried forward in particular by

the brothers Leon Krier and Rob Krier as well as by Aldo Rossi.

Laugier’s theory that columns should stand independently is said

to have influenced on Le Corbusier who used columns standing separate

from the walls. The preference for geometrical solids found in the

architects during the French Revolution is also the roots of the purism

of Le Corbusier. It seems as if Le Corbusier’s cube that had been

exhibited as a representation of purism was revived at this time, but in

fact the pure geometry of this typology had always something mystical

and had an aura. Here solids were self-asserting as objects and came

into conflict with each other.

Rossi remembered his own discomfort in the architectural

education that was an extension of modernism and created designs

emphasizing forms that had monumentality beyond function. In the Modena

Cemetery, he focused on the expression of monumentality with the use of

platonic solids by giving pure geometrical shapes like cubes and cones

to traditional Italian grave facilities (Fig. III-10). At the elementary

school in Fagnano Olona, he expressed by means of abstracting

geometrical shapes the authoritarian image of a large wall and a clock

which children use to have in mind for school building. Here was used,

as it were, a method of extracting architectural typology from the

archetypal image since his own childhood, which was the design principle

of giving shape to memory.

On the other hand, Leon Krier attempted to use pure geometric

shapes in order to reconstruct the urban space. He was active as an

architect who was particularly good at clear conception and sharp

theory. His proposal to install huge cubic frameworks at strategic

locations in the city center matched the appetite for monumentality of

the age. The idea of hollow cubes as a symbol of the city landscape was

realized by Johann Otto von Spreckelsen in the

“Grande Arche”

in Paris(1989) and by Hiroshi Hara in the

“Umeda Sky Building”in

Osaka (1993) (Fig. III-11, 12). In the genealogy of 20th century

architecture that was related to the cube, the cube here was turned from

a purist object into a colossal cube with monumentality.

There was an intention to profile and symbolize the urban squares

as solid spaces that had a social meaning as a result. Leon Krier had an

understanding that the exceeded freedom held by capitalist economies

brought about a confusion to the urban landscape, and his giant cube was

an embodiment of publicness and was so to speak an urban temple of the

20th century.

While it could be supposed that this transcendental form was

affected by the typology method of Stirling, and he found also a model

in Albert Speer who developed the architectural style of the Nazis as a

close aide architect of Hitler, and dared to publish a works of him. In

the post-modernist period that came into its own in the 1970s, there was

a trend to search for various wellsprings as alternatives to modernism,

and Nazi architecture was also one of them.

This was related to somewhat complex political nature and

aesthetic theory and was prone to misinterpretations. Particularly in

Germany, where sweeping away items related to the Nazis was a national

issue, there was nervousness about this type of action which might lead

to the return of Nazism. On the other hand, in other countries, the Nazi

architecture that had been taboo seemed to become paradoxically an easy

target of superficial journalism and could be reevaluated relatively

easily. Leon Krier focused on fascism as a way to rescue the splitting

and the chaos of the urban landscape marked by liberal capitalist

economics. This architectural style came to be seen as being able to

provide the symbolism that should be common to mass society. Although

the form of the

“rationalism”

of pure geometry had previously been used for the public manipulation of

mad political collectives, it was thought that the form alone could be

utilized as an effective social design method if the mad parts were

taken away.

Aldo Rossi can be otherwise called a new type of post-modernist

socialist architectural theoretician. He also tried to draw inspiration

from the socialist realism of the Stalin period (*1). Even in practice,

he revived partially the classical ornaments that had been rejected

during the 20th century and should have been swept away, and took such a

method as to put cubic forms that occupied locations like foreign bodies

in the urban space and to decorate them with cornices. This method was

even exhibited in the Italian palazzo architectural style of the

“Il Palazzo”

hotel built in Japan (Fig. III-13). The architectural style that Adolf

Loos had obtained through a method of simplification of classicism

during the initial stages of modernism returned in this period.

With this trend, the neoclassical architecture around the 1800s

such as Schinkel of Berlin suddenly grabbed the spotlight in addition to

Ledoux from Paris, but in terms of to what degree this

“rationalism”

of the 1970s was similar to the original neoclassicism needs to be

examined carefully. The reason is that the original neoclassicism that

emphasized rules and standards, and had, similar to Constructivism,

attempted to begin from the most abstract spheres and cubes against the

background of a new world view, would be supposed to form an beginning

stage of a new paradigm, and that this therefore resembled the character

of the period of modernism from the 1910s to the 1930s.

In fact, in the Krier brothers and Rossi is acknowledged the

trend to recreate neoclassicism based on sensibility rather than reason

and the attempt to find an intuitive sympathy for platonic solids and

pure geometrical shapes. This was equivalent rather to the mental

structure of the neo-renaissance and differed from the original

neoclassicism under the initiative of reason.

The

“rationalism”

of the 1970s resembled the

“Movimento Italiano per l'Architettura

Razionale”

(MIAR) that had supported Italian fascism and utilized the form of the

order of rationalism by irrational impulses and was incompatible with

the original scientific modern rationalism. The 1970s’ architectural

theory of typology that replaced the 1960s’ spatial structure theory was

understood for the first time in terms of this meaning and became a part

of rationalism in the 20th century.

(2)

Palladian classicism

As a method of creating spatial systems, rationalism is best

symbolized by a grid. The arrangement of columns is determined by the

intersection of checker-patterned lines arranged equidistantly along the

beam and digit directions. When the orderly arrangement of the columns

is broken by a deviation, manual intervention is required to change the

shapes of the beams. On the other hand, if it is considered as a freely

distortable and bendable space then a lot of manual intervention is

required. This was attempted by the form of organicism during the 1930s,

where it required a sophisticated yet flexible spirituality.

When Oswald Mathias Ungers consistently used the grid, it was

with a different intention from this kind of utilitarian rationality. He

also applied grids to areas where free design was possible and covered

everything in monistic spatial ordering. He even used stereo-grids by

doing the same not only for horizontal planes but also for elevations.

This was not merely a problem of the arrangement of columns and beams

there but became a curtain wall with smaller scale square grids.

Even when Constructivist design from the 1910s to the 1930s was

applied in the form of orthogonal three-dimensional coordinate systems,

this was an expression of the aspiration to reduce the degree of

freedom. There was born the Constructivist method to decompose volumes

into shape elements and to expand and reconstruct them. Compared to

this, Ungers' grids had the characteristic of simply reducing the degree

of freedom and tying up the building (Fig. III-14). The rigidity itself

had meaning. If the rationalism at the beginning of 20th century

searched for the new system as a norm longing for new freedom, then on

the other hand this grid rationalism asserted its own existence as an

isolated object for own purpose.

The installation of an unmoving object is the principal of

monuments. They were occasionally made of stone like an Egyptian pyramid

and became eternal existence. Although the spatial grid was nothing more

than a virtual form drawn in space, it made a deep impression and was

also a kind of monument that

became rooted in one’s consciousness. Just as the pyramids were simple,

monuments retained in the memory must be simple yet pure, and the

spatial grid also needs to have the most simple logic based on squares

and cubes. The grids that were extended up to losing functional

rationality and exceeded utilitarian comprehension could be even called

manneristic.

Ungers’ grid style of this kind was the complete opposite of

functionalism. If this formal rationalism were to be compared to the

moralistic efforts made toward the functional rationality of the early

20th century, it would be rather irrationalism. The fact that

“rationalism”

was advocated even by Aldo Rossi and the Krier brothers in the 1970s is

not something that should be understood supeficially (*2). In

architecture, formal rationalism has without doubt created a variety of

cultures throughout history. That is the architectural culture of

classicism that can be seen throughout the history of Europe since the

time of ancient Rome. The abstracted form of a grid is an important

indicator for understanding the classicism of the 20th century.

Even among the modernist architects, Mies van der Rohe in

particular frequently used grids that adopted transcendental, absolute

forms. This can be seen in particular on the external walls of high-rise

buildings and the grid ceilings incorporating a steel skeleton of

horizontal roofs covering large spaces. However, this is the result of

purpose-rationality under the guise of structural form, and the grids of

post-modernism as own goal had a fundamentally different character.

While post-modernism intended to revive an action of linguistic

signification by criticizing and breaking the neutral yet transparent

rationality of modernism on the one hand, the grids displayed an

autonomy which refuses such action on the other hand. The grids expanded

infinitely before the eye without any meaning.

In the Museum of Modern Art in Gunma by Arata Isozaki, a spatial

grid is used that includes slight variations from the rigid grid of

Ungers and that exhibits the transcendental feeling of the temple style

(Fig. III-15). Although it is packed with slightly manneristic elements,

the silhouette of the spatial grid itself forms a manneristic expression

of a modern rationalist temple. The words, coexistence of mannerism and

classicism, were actually used for Andrea Palladio who was active around

Venice in the 16th century.

Palladio was not an ironic mannerist like Giulio Romano. He

applied a wide variety of techniques of naïve classical ornaments and

introduced an order as a way of arranging them. The Villa Rotonda was an

incredibly famous work of formal rationalism that had the form of

central-plan with a circular hall in square plan and had four splendid

templar facades attached to its four facades. The glorious accumulation

of ornamental motifs of Palladio should have ended with a collection of

simple elements without the geometrical order of the plan, the column

axes in the elevations and a proportional system based on a

three-layered composition of classicism.

The play of mannerism seems to pull in always classicism. The

freedom of the parts get balance only after the systematic order of the

whole is obtained. As is unexpected, post-modernism stood on the balance

between the development of mannerism with rich sensibility on the one

hand and the classicism of formal rationalism on the other.

If we try taking away manneristic irony and critical methods, we

can see the world of formal beauty with Palladian grammar. In the series

of architectural works of Fumihiko Maki such as

“Tepia”in

Tokyo, items that directly use a grid, items that do not use a grid but

adhere to an orderly orthogonal three-dimensional coordinate system and

form an open system based on the methods of Le Corbusier can be observed

(Fig. III-16). There can be found a dimmension of aesthetic taste

resembling Japanese “Sukiya” architecture of tea house composed of the

formal grammar and its free performance. This resembled the classicism

of Palladio which adopted as its theme creating a formal syntax that was

easy for anyone to apply and promoting the individualization of works.

Maki again modernized the classical templar form in the National Museum

of Modern Art in Kyoto and displayed outright classicism while using

modern metal materials.

At the very start of the 20th century, there was the

neoclassicism of Behrens and Loos, and this was inherited by Gropius and

Mies. Then there was the classicism of the fascism of the 1930s, and in

a roundabout way, post-modernism also exhibits classicism. Although all

of these are classicism with cubes and formal systems as their theme,

each has a different meaning and background and is not the same at all.

Classicism exists as the axis of architecture. There could be seen the

broad-mindedness of classicism that it appears and disappears in time on

the surface and back following the fluctuation of axis, and displays the

flexibility to reflect the psyche of each age.

If we consider the classicism of the early modern times was the

employment of the styles of ancient Rome in renaissance age, then the

classicism of the 20th century is found in the more profound tradition

of abstract geometry. The beginnings are highlights in the Suprematism

of Malevich and the purism of Le Corbusier. Although Le Corbusier and

Mies were harshly criticized within the stream of post-modernism, a Le

Corbusier revival occurred in the architects of so-called New York Five,

etc., and the shadow of Mies was seen in the trends of minimalism. While

modernism was criticized on the one hand, on the other it was on the

road to becoming the classics.

The fundamental requirement of becoming the classics was the

original presence of the elements of classicism. The assertion that

there is actually a deep classicist spirit within modernism which

expanded freely and vigorously in a diverse way could invite

misinterpretation at the current stage where the 20th century is not yet

the distant past. However, the time will come when the modernist

movements of the early 20th century will be considered as yet another

form of classicism, in the same ways as the return to the classics

during the early renaissance of Brunelleschi and others was a movement

toward freedom from the scholarly academic system of gothic cathedrals.

The manneristic classicism from the 1970s to the 1980s made this

subconscious modernist classicism the visible classicism which became

the subject of the design operations of formalism.

Of course, 20th century classicism is not something that

recreates the ornamental system of classical order but is a return to a

more deep and original formal spirit. And therefore it derived a system

of forms by abstraction while drawing inspiration from sources such as

the simple stacked forms of the early romanesque and the vernacular

architecture around the area of the Mediterranean Sea including Africa

as well as the wooden architecture of Japan. The idea of grids can also

be considered a response to the demands of turning to classicism as a

most original means of space design.

(3) Hybrid system and

picturesque

The post-structuralist philosopher Jacques Derrida conceived of

the profoundly fascinating concept of

“deconstruction.”

This had a particularly strong effect on architectural design. This

concept was originally an attempt to highlight the new systematic image

in the process itself of dissecting and destructing the existing system

of modern rationalism, and it swept the world as a fashionable style

that was exhibited in the complex forms of buildings as if the view of

decomposing architecture itself had become fixed.

While critically inheriting from structuralism, he clarified the

dualistic structure of language culture created by humans, for example,

he contrasted the ideography called

“écriture” against the dominance of logical

and transparent phonograms. While structuralism highlighted the

structure and theory even within casual scenery and considered that

there could be found the subconscious order at the depths of reality

observed vague, Derrida criticized this kind of aspiration toward

structural order and attempted to restore humanity through the blood

that appeared by dissecting this like a terrorist.

The architects read into this message the means of destroying

monistic structures. First the structure of the grid was dissected

diagonally, and this was displayed symbolically using a method of

operating on the grid system by duplicating and overlapping offset axes.

Peter Eisenman sought the motif of the manipulation of shape in the

concept of deconstruction in particular by taking theoretical

architectural design as the theme. His method of combining squares and

cubes that had their roots in Dutch Constructivism finally resulted in

the composition of grids with offset axes and exhibited a display of the

process of shifting the logic of shape (Fig. III-17).

Richard Meier had indeed also used grids with offset and

duplicated axes, but he was more focused on their poetic expression than

conceptual logical evolution like Eisenman, and this was a manneristic

game that aimed to create an unexpected feeling of liberation at the

divide between two inconsistent systems (Fig. III-18).

Modern rationalism generally offered clear idea and made ideology

in order to create new society of 20th century, and built a posture to

go forward to the active reformation on all aspects to realize them.

However, this kind of rational reform had the unfortunate side effect of

wiping out indistinct cultural phenomena. In architectural expression,

the theme of universality was applied too much, and individual poetic

expression in particular was viewed as redundant and discarded. The role

of post-modernism was to revive anew the diversity and depth of poetic

expression as something indistinct.

This was consistent with the semantics seen, for example, in the

expression

“generating meaning”

within a homogeneous space. The orderly grid axes pursued by Mies were a

product of sound modern rationality, but a kind of autocracy of reason

occurred in order to build a consistent system and rejected

indistinctness as a result. Although Mies himself limited the job of

architects with the use of the words

“less is more”

and in particular attempted to leave a diversity of possibility to the

user and resident, the business-like architects of the industrial

society that was the epigonen of Mies often made effort to exaggerate

the existence of products of simple skeletal structures or to give an

aura, and the resident who was originally to have been given freedom was

sidelined. It is therefore believed that it is unavoidable for reviving

humanity to destruct the overly strong monistic systems.

On the other hand, attempts to destroy the order created by

reason can be undertaken by introducing foreign matter that is repulsed

by monistic order. It is sufficient to place objects that deny being

understood as part of the order within a neat grid. The typology of

Rossi that used platonic solids also had meaning with regard to this

point. The independent solids of cones, pyramids, cubes, spheres, and

cylinders produce a strong centricity when placed in the center of a

grid and often used for this purpose, and if they are placed off-center

then this instead produces a force that rejects systemization (Fig.

III-19).

If a foreign object that cannot be understood within a system is

to be introduced, it does not necessarily have to have a geometric

shape. It could be a symbolic shape that has meaning within itself as a

historical monument or even a freely designed shape, as long as the

placement has an unpredictability and suddenness that ignores the

context. Furthermore, it is probably also good if the person who

provides it is someone other than the architect that provided the

overall space system. This is because the mind that creates an element

that is mismatched with a system should think of creation in a different

context.

The large golden fireball-shaped object that Philippe Starck

placed along the Sumidagawa River of Tokyo had the characteristic of a

foreign object with such a meaning (Fig. III-20). This shape rejected

existing rational interpretation and did not match the context of the

city and can be viewed as the existence of some kind of meaning or

history. These objects held meaning only as occupying spaces as the most

opaque objects within a modern city which continues getting transparency

and systematization. This is able to function as a source to generate

meaning only by giving the feeling of a foreign object to the viewer and

makes the ordinary city scenery that has lost the ability to generate

meaning more inspiring. Although it seems that the environment and the

object are in conflict just like Hollein’s aircraft carrier floating in

the desert, in this case, the shape of the object floats between

abstract and concrete and defies any attempt to read a meaning into it.

When monistic order is dismantled, spatial systems themselves are

diversified, and the values of each of the groups of abstract, concrete,

and semi-concrete objects are reconfirmed, it is not necessarily true

that only one of the methods is valid, and it is also applicable to take

a mixture of all of the methods. This is best called

“eclecticism”

or the appropriate selection and application of mixing. From the middle

of the 19th century, although probably due to the evolution of

historicism into eclecticism, the gothic and renaissance and other

historical styles were catalogued and selected as appropriate for the

building type and purpose, and in some cases different interior styles

were even applied to different rooms of a single building. In comparison

to this, the range of eclecticism in the 20th century was the group of

geometric and concrete shapes that had been typologized, and the

paradigms of architectural design of the 20th century were reconfirmed

as being relatively abstract, formal concepts.

James Stirling was an architect who certainly grasped the new

eclectic principles that should be called

“typological eclecticism.”

In his

“Derby Civic Centre Proposal”

(1970) he had already typologized historical architecture such as by

building a historical guild hall in a courtyard surrounded by a

horseshoe-shaped arcade exhibiting modern-style shapes and placing an

assembly hall facade standing at an angle like a foundering ship (Fig.

III-21). Here, the post-modern historicism became the design of elements

floating in a contemporary urban space. This became a more abstracted

method in the

“Research Center”

in Berlin, where in addition to preserving the existing brick building,

adding an arcade like an ancient Greek store, a restaurant building with

Latin cross shape like a church, a lecture building like an

amphitheater, and a medieval castle-style building, it became a

composition with abstracted plans of various historical architectural

types (Fig. III-22).

This kind of method was overall presented like a parody of

historical architecture that was viewed as no different from a fantastic

medieval castle in the middle of Disneyland, and it seems also as if it

were a personal joke of the architect. However, this actually built the

basics of the logic of typology in the 1970s, and if it can be

understood that this was the result of the contributions of historicism

and eclecticism, then it is clear that this was an ideology created

through the process of transformation of 20th century architectural

theory.

This set of randomly scattered independent objects created an

overall scene rich in variations that delighted its beholders and was

reminiscent of the methods of picturesque. In the 18th century, in a

landscape garden with an artificial lake, ancient temples, ruins of

gothic chapels, grottos and a variety of follies included gazebos were

arranged, and viewing points and observation decks, and a site was

created to enjoy various elements and calm scenery. Something like that

revived against the background of the 20th century values. In the

“Neue Staatsgalerie”

in Stuttgart, Starling was based on the Berlin neoclassical museum of

Schinkel with a variety of historical elements inlaid at unexpected

locations to create a motif like a Le Corbusier’s work and was worked on

such that the scenery smoothly melted into a hillside of the urban

district (Fig. III-23). This resulted in a clever overall structure

exceeding a group of simple objects, with typological eclecticism fused

with landscape design. Such method was tied to the unique mannerist

aesthetics in the Museum Abteiberg by Hollein who mixed a group of

geometrical solids with the surrounding historical buildings and

landscape, implemented complex interior design utilizing the hillside

contours, and summarized these into a spatial picturesque that contained

all kind of changes.

On the other hand, in the

“Parc de la Villette”

contributed by Bernard Tschumi et al., a method was created of mixing

diverse elements such geometrical distributions of the site, axial

designs, a group of structures like follies arranged on the grid

intersections, a large spherical object like a memorial hall, a large

structure exposing its superstructure like a fragment of civil

engineering, and a 19th century style steel skeletal structure that was

preserved and renovated (Fig. III-24).

The urban garden that only opens out into a horizontal plane of

the past was transformed into three dimensional space and conversely the

structures were integrated with the gardening of

post-modern design feeling into

the unique form of a

“park.”

This new park concept that cemented the modern architectural design and

landscaping method also became a type of theme park that incorporated

the new technology known as the

“media park”

such as that demonstratied in the design competition in Cologne.

The meaning of the new picturesque of the 1970s and 1980s was a

continuing rejection of the perfect order of the early half of the 20th

century, but instead of returning to the 19th century, and instead of

creating an anarchist state completely lacking in order, a new dimension

was created that lay somewhere between order and chaos. Even while the

rational ordering of overall space was utilized as one method, rather

than being absorbed by order, objects and devices that created a

diversity of meanings were inlaid without losing the diversion.

If the creation of a park that displays this kind of modern

picturesque is turned into a single facade as is, it creates a new type

of decorative urban structure such as the

“Spiral”in

Tokyo by Fumihiko Maki. Here, the group of typological objects of grids,

cones, and staggered forms is attached with superb balance to an

asymmetrical wall with a slight fold (Fig. III-25). Although this could

also be referred to as a facade with a Japanese “Sukiya” feeling, it

also has a global universal common feeling of a two-dimensional

picturesque.

This kind of eclectic and picturesque phenomenon has an aesthetic

that shares diverse values and well reflected the process of advancing

designs since post-modernism. This therefore is thought to be comparable

with the fundamental tones of European eclecticism that featured

mixtures of diverse styles developed from the 1860s to the 1870s and the

picturesque asymmetrical residential buildings that started to become

generally widespread from then.

(*1) Aldo

Rossi, “Architettura della Citta”, Clup, Milano, 1987 (Japanese

translation by Tetsuzo Ohshima & Seiken Fukuda, Tairyudo, Kyoto,

1991)

(*2)

"Architecture rationnelle = Rational architecture", Archives

d'Architecture Moderne, Bruxelles , 1978.

> BACK