> BACK

revised on 2010.10.16

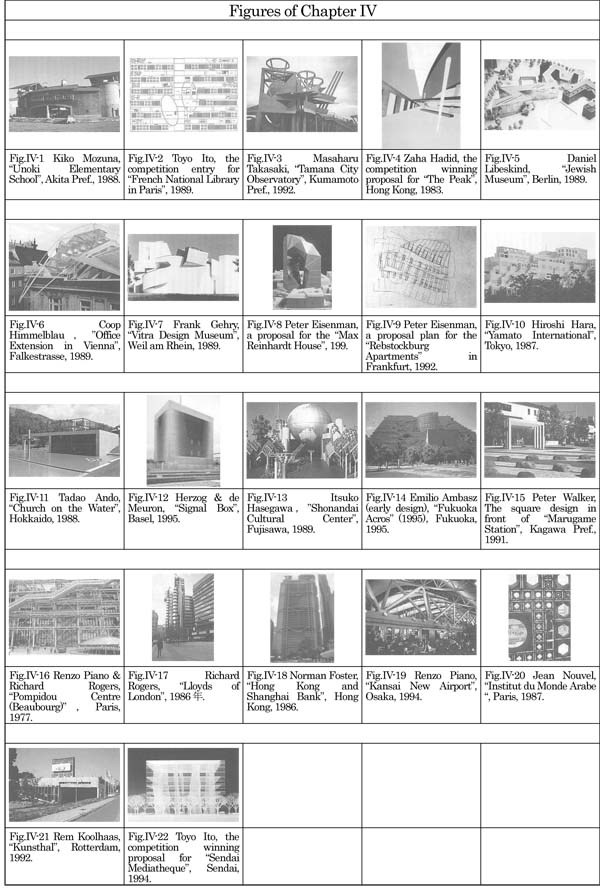

IV. Scene of maturity

8. Soaring

into chaos

(1) Ellipse and chaos formation

of neo-baroque

The aim of post-modernism was to first raise objection against

the monistic system brought about by modern rationalism. This negative

dialectic produced many breaks and fractures. The monistic system first

became dualistic and then pluralistic. New problems were brought in by

this process, and opposing paths led to either expanding this

pluralistic set of styles into chaos or reintegrating them into some new

method. The logic of style proceeded in this way.

This problem prompted the mannerism of the 16th century and was a

theme that occurred during the downfall of the ideal of the monistic

formal order such as the central-plan or proportions of the renaissance.

Michelangelo placed a semi-circular dome on the square plan of the

Medici chapel showing the posture to inherit the high renaissance in the

early half of the 16th century, and then he drew an elliptical shape in

the stone paving in the Piazza del Campidoglio showing the posture to

move to mannerism in the middle of the 16th century. This was used as a

trick that created a distortion in the field of view by matching the

trapezoidal square with the aim of creating the illusionary effect of a

perspective drawing method. After this, elliptical shapes became

extremely popular, such as in Piazza San Pietro in the Vatican designed

by Bernini in the middle of the 17th century, and elliptical shapes

became a key symbol of baroque style.

Arata Isozaki referred to and turned over this ellipse on the

Piazza del Campidoglio in the courtyard of the

“Tsukuba Center Building”

as if to present a doubled method of mannerism. Although it seemed not

to add intention to attach a role concerning the development of style

carried by the Piazza del Campidoglio itself, there was a boom in the

use of elliptical shapes after this through the 1980s and 1990s,

particularly in Japan. This was not a simple fad but can be said to have

symbolized the graduation of the awareness of the age from post-modern

mannerism migrating toward a baroque-ish stream of thought.

The

“Unoki Elementary School”

(1988) of Kiko Mozuna formed an elliptical structure surrounding an

elliptical courtyard as if reviving mysticism designs of the baroque

church and symbolized the universe (Fig. IV-1). Toyo Ito used the

ellipse in the

“Tower of Wind”

in Yokohama, and inserted in the competition entry for

“Bibliothèque nationale de France”

(1989) in Paris two elliptical shapes as if floating within a

lattice-shaped plan with an orderly barcode style (Fig. IV-2). The

architects group Coelacanth and associates added an elliptical shape

protruding from orthogonal coordinates in

“Utase Elementary School”

(1995) in Japan. Rem Koolhaas gathered the main conference facilities of

“Congrexpo”

(1994) into a single large elliptical shape in the project for

Euralille.

Although Isozaki himself created the overall silhouette of the

“Nara City Hall”

(1992 competition) using a long, thin elliptical shape and also used

ellipses in other works, the manneristic criticism was going to fade

away and the feeling of the existence of the elliptical shape itself was

emphasized just as in baroque age. The elliptical shapes gradually

developed into solidified objects and became a symbol of the age despite

the difficulty of constructing walls.

In the

“Color of the Crystal”

(1987) of Masaharu Takasaki, an egg shape appears in the corner of a

space that expands and sways. A variety of concrete shapes gathered

around the egg shape then appeared in the

“Tamana City Observatory Museum”

(1992), and the flow of power began to be visible on the surface (Fig.

IV-3). This was not already the critical spirit of mannerism but

exhibited the outpouring of the energy of baroque. In the “Naka-no-shima

Project “in Osaka (in the 1980s) by Ando Tadao, the insertion of a large

egg-shaped hall carved out of the interior of the former city hall of

historicism architecture was proposed.

Why was this flood of elliptical shapes seen particularly in

Japan? Although this is probably connected to the rapid pace of the

construction works in Japan, it may also be because the Japanese

architectural design world is more sensitive to the stylization of shape

compared to other developed countries and had strong inclination to be

influenced by that. The worldwide neo-baroque trend can be said to have

been superficially understood in Japan where it became a fashion.

So, where can we find the extent and main themes of the

neo-baroque style of the 20th century? Although elliptical shapes were

initially deformed circles, their transformation into even more complex

shapes continued, making it easy to wrap diverse shapes using the

efficiency of this deformation. This bore the role of an integration of

the group of isolated shapes which is inclined to fall into chaos. If

seen from the opposite viewpoint, it is said that the architectural

shapes each began to have individual power and fall into mutual

conflicts forming the tendency to the chaos.

Zaha Hadid proposed a new method of trompe l'oeil based on the

perspective drawing method that expressed unique distorted spaces (Fig.

IV-4). This was a dramatic expression drawn as a flowing space that had

an overly exaggerated feeling of depth and twisting space. This

neo-expressionist distortion incorporated a flowing energy rather than a

clear spatial system. The flow of power began to be created in the

expression of manneristic exaggeration and deviance.

The jagged style that Daniel Libeskind demonstrated in the

“Jewish Museum”

in Berlin (1989 competition) is a form designed after understanding

fully the meaning that the form has power (Fig. IV-5). The kind of

inevitability that this jagged shape has cannot be understood. The

reason is that it was the crystallization of the pure formal aspiration

as the result of rejecting regular spatial order and further advancing

the offsetting of axes. The space created internally enforced a large

amount of unexpectedness brought about by offset axes and without any

logic or consistency. In the interior of late baroque churches, bent and

cut-up entablature can be seen as if vanishing its original shape, and

in this case the broken shapes were expanded to the scale of a building.

Since the pictorial book of

“Micromegas", Libeskind revived the shape

motif of Constructivism of the 1920s, and progressed to more complex

structures attempting to draw wriggles as if life is created from a pile

of refuse. The results of this study of shape are displayed in the

“Jewish Museum,”

and the post-moder crushed shapes began to be infused with a new power.

Coop Himmelb(l)au expressed motion like crawling insects by

remodeling the rooftops on the historical town streets of Vienna using a

complex structural framework and glass (Fig. IV-6). The structural

elements have been put together freely, at worst like a garbage

collector of skeletal elements. It has a protruding forward edge as if

displaying a yearning for the freedom of romanticism. However, it is not

merely eccentric and displays a collectivity as if the life force inside

it were about to burst out. As can be seen in the case of Libeskind, the

group of elements mutually cooperate and begin to hold power greater

than a simple collection of matter.

On the other hand, in Vienna, which gave birth to the mannerist

and picturesque emotions of Hollein, there was the baroque emotion of

Günther Domenig. He had created the curving design of the

“Zentralsparkasse Bank”

(1979) that was like a can that had been torn open, and in the

“Steinhaus”

in Steindorf (1986), he combined a complex set of seemingly random solid

elements to create a structure like a bird’s nest. He also began to

destroy shapes that had order with all of his strength and reached the

stage of expressing a collision with a flow of power bursting out from

the inside.

Frank Gehry who had started from partial destruction of existing

building shapes also surpassed post-modern criticism and dualism and

shifted from focusing on the main shape that was destroyed to focusing

on the complex shape of the destroyer. In the

“Vitra Design Museum”

(1989), the modern shape that should have been destroyed had already

disappeared, and a wriggling accumulation remained as if individual

distorted shapes had collided. This created the feeling of the motion of

great power like an explosion (Fig. IV-7). The shape has no place to

relax and seems to be heading toward chaos. This was a replacement for

the valiantly complex set of decorations of the neo-baroque period that

appeared at the end of the 19th century, and here the 20th century basic

elements were transfigured, turning the structure overall into a

decoration of complex shapes.

In this way, the neo-mannerism of post-modernism turned into a

neo-baroque stage. The chaotic shape itself became its own purpose, and

all that stimulate the sensibility which have been set free by

post-modernism are further accumulated into the figure of building.

The neo-baroque of the late 19th century left behind monuments

that were luxurious yet overpoweringly over-decorated like the Opéra de

Paris, the Palais de Justice in Brussels, and the Berlin Cathedral.

These had the mission of decorating the capital in an age of imperialism

and came to symbolize the wealth of the nation. The social background of

the 20th century neo-baroque was completely different, and through

globalization, the themes of the pride of the nation, etc. became

outdated. However, apart from the expression of the trend displayed by

the leading design, anyone could

guess that the buildings that took this kind of expression of power as

their theme were set to reach the stage of buildings that captured the

attention of the public.

The expression of power seems to be displayed not by production

power and societal wealth but by an expression of the power of life as

per today’s meaning. The expression of the power of neo-baroque could be

established as an extension of an object that resists systemic society

such as solids like the foreign body of Rossi or the fire ball of

Starck. That, even among elliptical shapes, not just simple elliptical

domes but egg-shapes like the objects of Takasaki were used, suggests

that the shapes which symbolize the power of life are sought surpassing

the world of geometrical shapes. On the other hand, it is teaching that

even a metaphor of a delicate and faint vitality such as a simple

swimming ellipse form like a paramecium designed by Ito has a bud which

reclaims the new time.

(2)

Complexity as logic

The mathematician Mandelbrot proposed a fractal geometry that

focused on the relationship of the similarity between parts and the

whole called self-similarity and shocked the world with its epoch-making

mathematical theory. In the world of architectural design that is not

very far removed from Euclidean geometry, this existed as a shape with a

completely different principle from conventional architectural shapes.

And furthermore because it was able to be simulated by computer

graphics, this was welcomed expecting to lead to new design methods. It

was felt that the complex shapes of mountain ranges and coast lines

created naturally were actually the logical result following some rules,

and these could be recreated by the hand of man, and new design

possibilities came into view.

Architectural design is a synthesis of shapes created from

Euclidean geometry and freehand artistic processes such as decorations.

The existence of that scientific aspect of reason and this artistic

aspect of sensibility became the foundation for the wide development of

architecture. Architects could be scientists while being artists and

produced a diversity of expressive styles by combining the two. Fractal

geometry is therefore thought to have enabled sections that were viewed

as freehand decorations to be incorporated into the realm of geometry

and handled theoretically. At the very least, fractal shapes, in other

words the unintended and irregular shapes as if fragments were

collected, were not necessarily unattractive, and the value of

architectural formal beauty was reviewed.

Eisenman quickly caught onto these conditions and rapidly

attempted to incorporate complex shapes and unexpected shapes from

computers into architectural design. In the proposal for the

“Max Reinhardt House”

(1993), the large standing arch-shaped building was designed by using

the method called “folding” (Fig. IV-8). This form could be interpreted

upon the extension of post-modernism as such that the method of offset

axes was repeated and having reached a shape that is a tangle of a

multitude of axes. At the same time, it can be seen as such that the

self-organization of shape by self-power and logic was able to present

an expression of self-power and can be interpreted as a baroque

formation as an expression of life force.

In a proposed plan for the Rebstockburg apartments in Frankfurt

(1992), the individual buildings were defined from the overbearing

overall shape, starting with the folded-up ground surface and complex

silhouette of wrinkles. The street arrangement created by this has

resulted in an arrangement of buildings covered by irregularly leaning

walls as if within a reef on the coast (Fig. IV-9).

Even if attractive irregular shapes can be produced, the folding

method restricts the freedom of the architect and forces him to follow a

constant logic. Therefore, although the shapes have the same distortion,

for example freehand formations such as the organicist structures of

Aalto, they differ from the starting point. However, the aspiration to

the same organic structures functions and comparison is useful.

Eisenman started from Constructivism and continued to experiment

with offset axes while attempting to escape from inorganic forms and was

gradually led to complex forms that did not highlight any homogeneity.

Just same as Aalto had a will to exceed the geometrical tendency of

modernism from the romantic mind in the 20th century, Eisenman is

graduating from monotonous geometry. Whereas Aalto found his outlet in

the free-form which is released by intuition from the organic brains of

human beings, Eisenman found his outlet in the complex shape appearing

logically as an extension of scientific theory. Eisenman wanted not to

be a poet surrounded by the natural environment but a Dadaist poet

supported by scientific devices.

Architectural historian and critic Charles Jencks attempted to

interpret modern architecture as per the motif of scientific vision

grouped with recent complex systems of science in

“The Architecture of the Jumping Universe (*1)”

(1995). He supported the idea that a metaphor of scientific vision was

expressed in architectural structure, and the interpretation was open

from Eisenman to Gehry and Zaha Hadid to Calatrava and Correa. The

architecture historian Sigfried Giedion theorized architecture as a

space-time design by applying Einstein’s theory of relativity,

demonstrating the belief that there was a shared base between the

transitions of modern scientific advancement and architectural style.

Certainly, as Jencks said, it is clear that there is a relationship that

cannot overestimate the gap between the rapid appearance of complex

systems of science and structural theory in architectural design.

Hiroshi Hara designed buildings with complex skylines, such as

“Yamato International”

(1987), and showed examples of a formal system of fractal nature that as

the parts were fragments and acted free the total form has not an

overall tidy silhouette and become the jagged style (Fig. IV-10). He

portrayed buildings as mica with stacks of thin plates and expressed the

disordered forms of detached silhouettes as architectural shapes. The

glass walls of the internal corridors were covered with small paintings

representing the complex shape structure, and this mixed with the

fractal nature of the clouds in the sky and trees in the forest that

could be viewed through multiple panes of glass to foment a multilayered

space lacking homogeneity in depth.

Hiroshi Hara applied mathematical theory to architectural design,

and in his book

“Space <From Function to Modality>”

he presented vagueness, depth, and stagnation as space enveloped in a

fog, using the term

“modal logic”

(*2). Because of his criticism of Mies’ aspiration to homogeneous space,

he took non-homogeneous space as a theme and carried out mechanisms for

operating on stagnant or congested multi-layered spaces and arrived at a

unique spatial theory.

This kind of design method demonstrated a different procedure

from the architects of Europe and America who had come to express

complexity as a group of distorted shapes extending the structures of

Constructivism. Although he originally took architecture as an

artificial device, like the designer of a mechanical device, he arrived

at the idea of complex structures like a village from the field work of

structural analysis on villages described earlier and adopted the

construction of delicate and complex spaces as a theme by studying the

entanglement of the depth, density variations, and scenery of diverse

elements in a village space within nature. Thus it seems that, in spite

of his critique on the monotonic logic, he continues the challenge of

modern reason to propose an even more sophisticated logic.

Operations that had been undertaken by the artistic intuition of

the right brain were replaced by the logic of the left brain. Natural

spaces which experienced a lot of evolutions and historic spaces which

experienced civilizations do not have any homogeneity but have infinite

complexity and changes, which Hara grasped with the word “modality”, and

aimed to assemble architecture as a device for artificial reproduction

of it. Here the subject of design is the interior space or the air

covering the buildings itself, but the things that an architect can work

are only the walls and roofs that frame the space, and therefore some

intelligent contrivances were incorporated.

The forms of the late-baroque churches consisting of curving and

intersecting ceilings, and variously assorted intertwined groups of

decorations creates diffuse reflections, shadows by the transparent

sunlight penetrating through the windows. Furthermore, the delicate

structure and complex decorations of late gothic churches had an

interior space with differences in density due to light penetrating into

a dark space through stained glass. These contrasted with the

homogeneous space created by the clear shapes of the renaissance formed

from orderly proportions and member structures. The complexity of mixing

a variety of structures was a means for presenting the depth of the

space.

When spaces with floating

objects and particles like mist that cannot be grasped by hands became

the subject of design, architects are forced to embark upon an endless

process of creation impossible to reach the goal of making shapes. This

was originally a comprehensive art that included the works of many

artists, engravers, musicians, etc., as in the case of gothic

cathedrals. There was also the idea that architects should not intervene

to that extent. However, as in the late-baroque small churches of

southern Germany, it was acceptable for the architects themselves to

undertake all of the presentation and creation as if carried out by a

person who was simultaneously an architect, engraver, and artist. The

theme of the age of chaos becomes the integration of pluralistic values.

The science of complex systems has taught that complexity can be

presented using simple devices, and this indicates that the presentation

of chaos by a single architect is not impossible.

In the mathematics of chaos, even phenomena that are considered

to be complex at first glance can be understood as a repetitive

phenomenon that occurs by taking something called an attractor as the

axis and introducing a constant fluctuation in its vicinity. Thus, it

was confirmed that a phenomenon that had disorder could be reproduced by

simple equations alone. The contrivance of this kind of device is an

issue for the architects of the time when complexity is the theme. The

thing Eisenman had attempted to produce through the simple logic of

folding was not only the complexity of the architectural form itself but

the complexity of the space and scenery produced by it.

At the beginning of the 20th century, to be scientific and

theoretical meant to simplify the spatial form and therefore to

reconstruct architecture as an effective residential machine using

simple logic was attempted. Now, the idea has reversed and complexity

has become the goal, and we are beginning to walk on the path toward the

other extreme, the impossible complexity. This is the so-called Karma

that man has borne since starting to resist God as homo faber (man the

creator) and is the infinite path of continuous creation as long as

man’s desire last. In the same way as baroque had continued to seek that

ultimate expression up to the end of the late-baroque, now architects

who are aware of complexity in design can do nothing but to adopt as

their theme unending supreme complexity.

(*1)

Charles Jencks: "The

Architecture of the jumping universe",

London/ New York, 1995.

(*2) Hiroshi Hara, “Space 〈From Function to Modality〉”, (Japanese) Iwanami-Shoten, 1987.

9. New

paradigms in embryo

(1)

Ecological naturalism

When it has become understood

that man-made objects posed a menace to the nature, changes even the

atmosphere and could turn the earth into a place uninhabitable by life,

the contemporary arguments on ecology were taken on with a sense of

urgency. Freon gas is destroying the ozone layer and allowing

ultraviolet rays to reach the ground. The imbalanced emissions of carbon

dioxide gas leads to global warming, the polar ice caps melt, the cities

along the coast are flooded due to the rising sea levels and the

climatic become disordered. To face this huge crisis, man could mealy

review modern civilization and change his lifestyle. In this regard, it

seemed like there were nothing that architectural design could do.

In every age throughout history, people have come to reflect the

problems of their time in architectural style. Even the choice of

temples, cathedrals, or palaces has become a means of symbolically

resolving the dominant themes and problems of each age. Even in modern

ages, the ideas of modern rationalism could be said to have led to the

current architectural styles. The architectural styles produced by

modernism were examples of such 20th century. The fact that new

architectural styles will again be created in this way in the 21st

century cannot be denied, and it is strongly predicted that it will be

closely related to the theme of ecology.

What ecology aims for includes a thrifty lifestyle with a

reduction in the consumption of resources as much as possible, and also

a change from a civilization that completely dominates animals and

plants to one that coexists with them. At the end of the 19th century,

while society progressed toward the wastefulness of the neo-baroque

period after the industrial revolution, there also appeared a trend

toward naturalism and socialism that resisted this. The psychological

structures of today’s society can also be said to resemble this age in

some respects. Although there is no argument that ecology is a

contemporary naturalism, it needs moreover to be confirmed that this

bears the same motives as the naïve socialism before the Russian

Revolution.

Therefore, we should focus on William Morris who wrote

“News from Nowhere”

(1890, 1893) and is known as an artist of the arts and crafts movement.

“News from Nowhere”

is a novel about a place where people with a high level of crafts live

happily on a fictional island far removed from civil society. His ideal

was that the traditional crafts should be maintained and developed, and

therefore he criticized the bland mass-produced goods manufactured by

the mechanical production of those days. This was summarized in the

categories of utopian socialism and artistic socialism, and he was

viewed as a dreamer, while there was the radical socialism of Marx that

concluded that social revolution is needed to transform the economic

system. Morris, who thought that traditional values were important,

formed the

“Society for the Protection of Ancient

Buildings”

to start an active movement to preserve historical buildings, in that

was included not a simple nostalgia but a vision for a future society

with craft as the intermediary.

The thesis of the art historian Nikolaus Pevsner regarding the

mechanisms of the occurrence of modern design is widely known, that the

movement which rejected mechanized civilization and promoted hand work

was eventually adopted by the Bauhaus school opened in Weimar with

Gropius as the director in 1919 and was transformed to the applied art

in 20th century of mechanical production based on hand work. By taking

that in thought, envisioning a Morris of the age of ecology, we can

conceive of the direction of modern craft and architecture. Morris was

the image leader of the arts and crafts movement. Among the artists who

gathered around him was an architect Philip Webb, who designed the

Morris’ residence“Red

House”

whose interior design Morris himself had worked on. His standpoint is

remarkable and helpful to think about today’s world of architecture.

Webb mainly designed houses, and these were modest, relatively

inconspicuous structures. While they were based on a traditional rural

residence style, they utilized modern geometry, as can be seen even in

the circular windows of

“Red House.”

That is acknowledged also in a geometrical design of

connected small triangular gables in other houses. Thus, a return to

tradition and budding modernism existed simultaneously. Thus, the key

themes were the rejection of the aspiration for an abundance brought by

the industrial society and the rehabilitation of the handwork of man.

The idea of today’s ecology that is recognizing the limits of a

consumerist society is thought to apparently highlight things

corresponding to hand work. This does not refer to the simple revival of

some traditional work of craftsmen but indicates that the human body

action of present days has the direct contribution to the design in the

meaning that the Bauhaus started from handwork and shifted to the

industrial design.

Tadao Ando limits his design vocabulary to the flat walls made of

exposed concrete, exposes the structural substance against the human

body, and constructs it with natural elements directly provided by

nature in the form of light, wind, and water , removing artificial

designs from spaces (Fig. IV-11). In

such method can be seen the composition which could expanded to the idea

of contemporary ecology. The

second half of the 20th century could be said to have created a

mainstream trend to change architectural shapes into something complex

as is known in the move toward post-modern diversity and complexity.

Thus, the style of Ando resists the flow of time as if pulled out and

left behind by 20th century technology and the industrial civilization.

However, the antithesis of this is the formation of the kind of

architects who design low-cost public housing and gradually developed a

different flow from the mainstream industrial and consumerist society.

Although this aspiration for simplicity was also highlighted in

the geometric designs of Louis Kahn, for Kahn design started from a kind

of heroism like a temple and there was the theme of the projection of

divine shapes that were in the ideal of neo-Platonism of the

Renaissance. On the other hand, for Ando design started with tenements

that were a place of people’s living and widened the small space

touching the flesh as if expanding the model, and that differed from the

things of divine structures at the beginning at all. While, as is

previously noted, the style of Kahn included the logic of spatial

structure theory of those days, he took besides a direction that

transcended from the flow of the age toward complexity and settled on

simplicity to the point of clumsiness. This became deeply popular with

people who criticized the industrial civilization and consumerist

society of the 20th century, and it was also hailed by leading

post-modernists. Ando studied the space designs of the purism of Le

Corbusier and absorbed the simplicity of Kahn and incorporated these

into a unique ascetic and frugal psyche comparable to the Order of

Cistercians.

In order to understand the state of current designs, one must

delve further in the comparison between the arts and crafts movement and

Ando. Just as there is a mutually complementary relationship between the

fashion designers of clothing accessories and the bare concrete

architecture of Ando, it is possible to envision a similar dichotomy

between Webb and Morris. If we consider Issey Miyake’s designs of pleats

that aim at clothe design for the ordinary people, the shadow of the

arts and crafts movement can be seen in current fashion.

One type of design that rejects complexity and abundance is the

architectural style called Minimalism. The architecture of Herzog & de

Meuron cut back on so many elements that one might think the structure

wasn’t complete. After everything that could be removed was removed and

the shape was simplified as much as possible, only box-shaped buildings

remained like a thin wrapping (Fig. IV-12). The structural game of

post-modernism of aiming for complexity was seemingly completely

unrelated to them. While in post-war Germany, after reflecting on too

excessive cultural policies of the Nazis, architecture came to be viewed

as a technical work giving distance to an extreme from artistic

contemplation, the effects of this rational aesthetic probably also

extended to the Switzerland.

In a series of works of the Minimalist architects, the barely

remaining skin of the building was not merely a facade but was

transformed into a device that incorporated high technology. Differed

from Ando’s plain concrete walls as if expanded from crafts work model,

the remaining wall becomes a minimal mechanical device that represented

the final stage of the machine model age of the 20th century. Compared

with the fact that the same Swiss architect Hannes Meyer’s had sought an

architectural image like the manufacturing mechanism of factories, in

this case the mechanical thing had changed into a small device that

combined information machines. The cube of Purism that was the origin

for Le Corbusier, who also originated from Switzerland, was recreated as

Minimalism, using completely different materials. It was as if the ages

had transpired in a loop.

By the way, contemporary

naturalism has rediscovered the globe. From the ideas of geometrical

typology, platonic solids that are simple geometrical shapes were

preferred and the architecture of spherical form by Boullee and Ledoux

during the French Revolution came to be reevaluated. This could be seen

in spheres such as the mirrored ball in the Parc de la Villet in Paris

as well as the

“Shonandai Cultural

Center”

(1989) in Japan by Itsuko Hasegawa, which also symbolizes the globe

(Fig. IV-13).

The globe was not only used as a visible symbol, but also people

began to be aware of the earth as being embedded in the globe. Emilio

Ambasz proposed architectural spaces buried in the green ground from an

early time, and against the background of the changing global awareness

that led to a review of the world’s environment, he brought to life

buildings such as the

“Fukuoka Acros”

(1995) (Fig. IV-14). Peter Cook who had viewed cities as mechanical

devices as a member of Archigram became noticeably romanticist since the

“Urban Mark”

project of the 1970s, where he has covered mechanical devices with green

and transformed them to an organic landform like a hilly district. This

displayed an awe of the natural power of the globe that far exceeded the

wisdom and knowledge of humans.

This growing interest in the planet Earth caused the appearance

of new types of landscape designers, like Peter Walker who sought new

methods for designing ground surfaces. He fused the tradition of the

geometrical gardens of continental Europe with the American method of

urban park design that incorporated the wild nature and perfected a

design style to display like a

garden and also like an urban plaza (Fig. IV-15). Even genres that

emerged in the post-modern age of the

“Park”

of the Parc de la Villet that merged eclecticism and picturesque

exploited a theme that can also be called the architectural version of

land art through geometrical segmentation of the ground and buildings

that grew from within the earth. The awe of the Earth that was the

subject of art while preserving the ground surface was fostered here,

and the age of the global environment was crystallized into one style of

architectural and urban design.

(2) Technological architecture

and information space

A criticism of the mechanical civilization of the 20th century

germinates the idea of ecology on the one hand and searches for a leap

toward a relatively advanced technological civilization on the other.

The latter is brought about by information technology, and this leads to

a deep paradigm shift that did not merely stop at the production and

utilization of simple computer devices.

Compared to the machines of the 20th century that were nothing

more than moving devices that replaced the human body such as the

railways and machine guns exalted by futurists, information devices

later began to replace the human mind and robots became a reality.

Although the clumsiness of buildings of modernism architecture and

functionalist architecture was criticized during the post-modernist

period, one aspect of that unfulfilled expectation appeared solvable

with the appearance of relatively superior architectural technology and

planning methods. The architectural image that modeled machines

progressed step by step in this way. The progress of technology was not

complex like the advancement of culture that followed fluctuation

phenomena, and overall this was also not affected by the games of the

spectacular formal styles of post-modernism.

Renzo Piano and Richard Rodgers accepted the assistance of the

structural engineer office of Ove Arup and Partners in the

“Pompidou Centre”

(Beaubourg) and inherited the ideas of device-like structures of

Archigram. Although the idea of surrounding a pillar-less main space

with devices as a secondary space was that from the age of spatial

structural theory, this experiences the technical development as a more

effective mechanical device (Fig. IV-16).

In the

“Lloyds of London”

(1986) by Rodgers himself, many see-through elevators surrounded an

office space, presenting an architectural image that got more closer to

a mechanical device. The ducts were incorporated with the proportional

design of the walls, and the roof was equipped with a colorful gondola

crane for cleaning the wall surfaces (Fig. IV-17). Norman Foster also

presented a new style of a high-rise office building where a

mega-structure is sandwiched with elevator shafts in the same way in

“Hon Kong Shanghai Bank” (Hong Kong, 1986) (Fig. IV-18).

Those called as

“high-tech style”

architects who took an independent route from the

post-modernistic trend toward sensibility, gave effort on its extension

combining information devices into the building to meet the technical

progress. They combined also to that an interest in ecology, and merged

the seemingly contradictory directions of information technology and

ecology, i.e. future technology and criticism against modernism.

Although they continued to use reason as more of a foundation than

sensibility and steadily inherited modern rationalism, they were already

far removed from the heavy industrial mechanical models of the Italian

Futurists and Russian Constructivists. They made even high-rise

buildings more light-weight changing from iron to aluminum and gave

flexibility allowing wind to blow past large glass surfaces and thin

columns.

Piano presented an architectural image like a thin long vessel

turn over on water surface and designed cross-sectional shapes that

followed the flow of internal waving winds in the

“Kansai International Airport”

(Osaka, 1994) (Fig. IV-19). Trees were even planted beneath glass in the

void space excluding demonstration of the rustic structural beauty in

buildings. The old heroic architectural image was hidden in the shadows

and the silhouette was not determined purely by structural dynamics. At

other occasions also, the interests of their technology-oriented

architects demonstrated the clear move toward an ecological age,

creating a natural flow in the interior room, actively introducing

energy-saving technology, etc.

Computers are useful for

environmental control and can operate air conditioning devices that

create an optimal environment based on changes in sensor temperatures.

Jean Nouvel proposed a glass wall that employed the aperture technology

of cameras in order to adjust the amount of heat in the incident

sunlight in the

“Institut du Monde

Arabe

” (Paris, 1987)

(Fig. IV-20). This was a monumental work in terms of the transformation

of the walls into an elaborate mechanical device controlled by

information equipment, which are no more merely thick stone, brick

chunks or clear glass. Architecture was increasingly becoming something

other than just buildings.

In recent times, the common definition of architecture has

progressively changed. The architectural image changed in the 19th

century to light structures based on the structural theory of steel

skeletons, to moving mechanical devices in the 20th century and has now

begun to be transformed to robots. The ideal of Greek temples where

columns stand neatly in line and supported heroically is already

becoming a thing of the distant past. Furthermore, information

technology is changing the common perception of the architectural image

inside the computer display.

The appearance of two-dimensional computer graphics (CG) has

enabled computer-aided design (CAD), the drawing board continues to be

expelled from design offices, and the further appearance of 3D CG

(three-dimensional computer graphics) is bringing about an age of formal

design in the depth of display. Architectural shapes created in virtual

space have no relation to the gravity any longer, colors are so clear

without knowing the shadowing, and assemblages of platonic solids called

primitives are placed as if dancing in space. A real feeling of distance

has been lost and the economic concept of space has also faded with the

architectural figure beginning to slide in an unexpected direction.

This kind of idea was displayed in a series of architectural

works by Rem Koolhaas. This was based on the Constructivism of the De

Stijl style that could be called the Netherlands’ tradition, and put

into three dimension, with walls and object elements combined as if

suspended in air and framing space (Fig. IV-21). In his competition

entry for the

“Bibliothèque nationale de France”

in Paris (1989), there was a large void that resembles a cube, and

several masses of curved objects were suspended in it. Cubes have become

nothing more than transparent boxes any longer, and the shapes have lost

the feeling gravity and no longer supported stably by the ground or

floors. The similar idea of a group of objects in three-dimensional CG

space was even displayed in the

“Kunibiki Messe(Shimane Prefectural Convention

Center)”

(1993) in Matsue city by Shin Takamatsu.

The method making buildings’ frames flat, purifying the surface

using metal, and making transparent with glass on the one hand, and

scattering small rooms and devices in the interior space as if separated

from building on the other, was employed by many architects of the new

generation. A building can be said to have become a production of shared

and institutionalized method rather than a profound art that creates

personal masterpieces. Buildings are made into membranes on the one hand

and turned into interior design on the other.

The theme of

“membrane”

of architecture is reminiscent of the theorization in

“Der Stil”

written by Gottfried Semper in the 1870s. This sublimated into something

that should be called texture mapping architecture, like attaching

floral wallpaper to a building facade as in the

“Majolika Haus”

by Otto Wagner at the end of the 19th century. The phenomenon of

transformation to membranes is also recognized to occupy a fixed

position within the cyclical changes of architecture. In the late 20th

century, display devices corresponded to buildings transformed to

membranes and images represented in three dimensions are interior

design. If we envision this model of the display device being expanded

to the scale of a building, the effect of three-dimensional CG on

architectural design can be understood.

The space within the display has come to replace the work of

creating an image processed within the mind of the architect. A computer

works instead of the brain and is considered literally as electrical

brain. The things imagined by the mind are immediately made concrete

within its display and come together as a transformed shape. This has

led to the need for a third medium occupying the space between the mind

and actual space, such as the new concept of virtual reality.

The method of perspective drawing led to a paradigm shift in

architectural shapes during the early renaissance. This method came to

be ignored during the drawing method revolution of Cubism and mechanical

axonometric drawing method in the early 20th century, and furthermore it

was revived as the digital perspective in the form of three-dimensional

CG. Three-dimensional CG in wide meaning utilizes also the ideas of

cubism and can be said to have been integrated by combining this with

the ideas of the perspective drawing method. It is hard to say that this

new perspective drawing technology does not lead to a strong paradigm

shift as influential as the renaissance.

It is also difficult to predict how far this will develop the

unknown architectural image. One possible direction is the special

ability of CG to draw mysterious curved solids using spline curves

besides platonic solids. The free curving membrane design that follows

the flow of the wind as realized by Piano in the Kansai International

Airport was similar to this. It is indeed enough when plenty of parts

with the same dimensions were produced if the roof is made as a neat,

plain surface. But for a gently curving surface, multiple parts with

various dimensions are need to be produced, because there is no

difference that it is assembled with many steel members. However,

factories that have been robotized by mechatronics can implement such

intricate requirements. Here the mind sticking to common sense on design

and producing cannot follow the rapid development of the age.

The

“Sendai Mediatheque”

(1994) by Toyo Ito destroyed the conventional knowledge of columns (Fig.

IV-22). It only had a scattering of pouch-shaped nets freely expanding

and contracting, without a neat row of columns or pillars. Columns

escaped from their typical form in the 20th century as symbolized by the

pilotis of Le Corbusier and dissolved to become tubes which can be drawn

from spline curves. In the age of Art Nouveau, Guimard turned columns

into objects with elegantly curved surfaces appearing as if melted in a

solvent. Art Nouveau completely destroyed the common sense of the 19th

century at this point. Also, the common sense of the 20th century that

started with Cubism seems to be collapsed, while leaving the same mark

of these melted columns.

Spline curves, by nature, are drawn joining gradually multiple

points. Therefore, unlike the minimal amount of information determined

only by the radius of a circle and the length of a column such as the

columns of Purism, many three-dimensional coordinates need to be

provided in case of spline curves, and the amount of information

required is large as a result. This should be called as complex shape,

and that can be considered the antecedent of the aspiration for

complexity that was prominent at the end of the 20th century.

On the other hand, the

silhouettes of Ito’s architecture displayed a simplicity common with the

Minimalism of glass cubes. The aspiration for simplicity and that for

complexity are dissected within a single building’s shape, and the age

of the 20th century is summarized. In any case, during the early 21st

century, it is expected to be a confrontation between complex shapes and

simple shapes just as Behrens showed once upon a time with two streams

of Art Nouveau and neoclassicism.

> BACK