Ichiro Imae's Innovative Green Research

for Environmental and Energy Nanomaterials

i3 GREEN Group

Department of Applied Chemistry, Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering

Hiroshima University

for Environmental and Energy Nanomaterials

Converting Wasted Heat into Electricity — Development of Environmentally Friendly Organic Thermoelectric Device Materials

Creating a Comfortable Indoor Environment by Controlling Light — Research on Smart Window Materials

Decomposing to Create Value — Research Aimed at CO2 Reduction and the Creation of High-Performance Carbon Materials

Capturing and Degrading — Tackling Water Purification Materials through Two Approaches

Energy derived from natural resources—such as petroleum, coal, and natural gas, known as primary energy—is widely used in power plants, automobiles, industrial facilities, and waste incineration systems. However, nearly two‑thirds of this energy is ultimately released as heat and dissipated into the environment without being effectively utilized.

Importantly, around 80% of this waste heat is low‑ to medium‑temperature heat below 200 °C. Although part of it is reused for applications such as hot water supply or heated swimming pools, opportunities for effective utilization remain limited. Against this background, thermoelectric conversion has attracted growing attention as a promising technology for energy recovery. Thermoelectric systems can directly convert heat into electricity without the need for mechanical components such as steam turbines, enabling power generation with simple, compact, and reliable device structures. In addition, thermoelectric devices can operate using small temperature differences and small‑scale heat sources, including wearable devices, smartphones, and even the human body.

Image credit: NASA Source: NASA

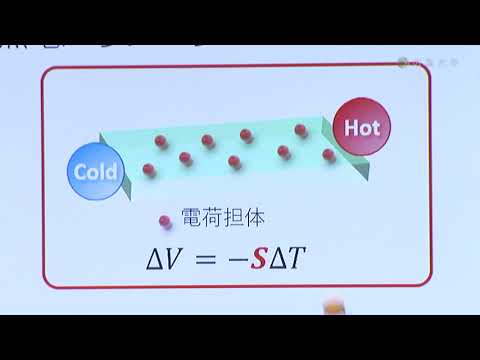

Conventional thermoelectric technologies have primarily relied on inorganic materials. Indeed, inorganic thermoelectric generators have been successfully implemented in space exploration missions, such as the Voyager probes. However, materials capable of efficiently converting low‑ to medium‑temperature waste heat remain underdeveloped. Furthermore, some inorganic thermoelectric materials contain rare or toxic elements, such as tellurium, which pose challenges for large‑scale and sustainable industrial applications. To address these issues, increasing interest has been directed toward the development of organic thermoelectric materials. In thermoelectric devices, applying a temperature gradient induces a redistribution of charge carriers within the material, generating an electric potential that can be harvested as electrical power. Efficient charge transport within the material is therefore a key requirement for high thermoelectric performance.

Organic compounds were long regarded as electrical insulators. This perception changed fundamentally in the 1970s with the discovery of electrically conductive plastics, now known as conducting polymers. The emergence of conducting polymers opened new possibilities for thermoelectric applications based on organic materials, and systematic research in this area has progressed steadily since the 1990s. Today, this field is rapidly expanding through intensive research efforts at universities, research institutes, and industrial laboratories worldwide.

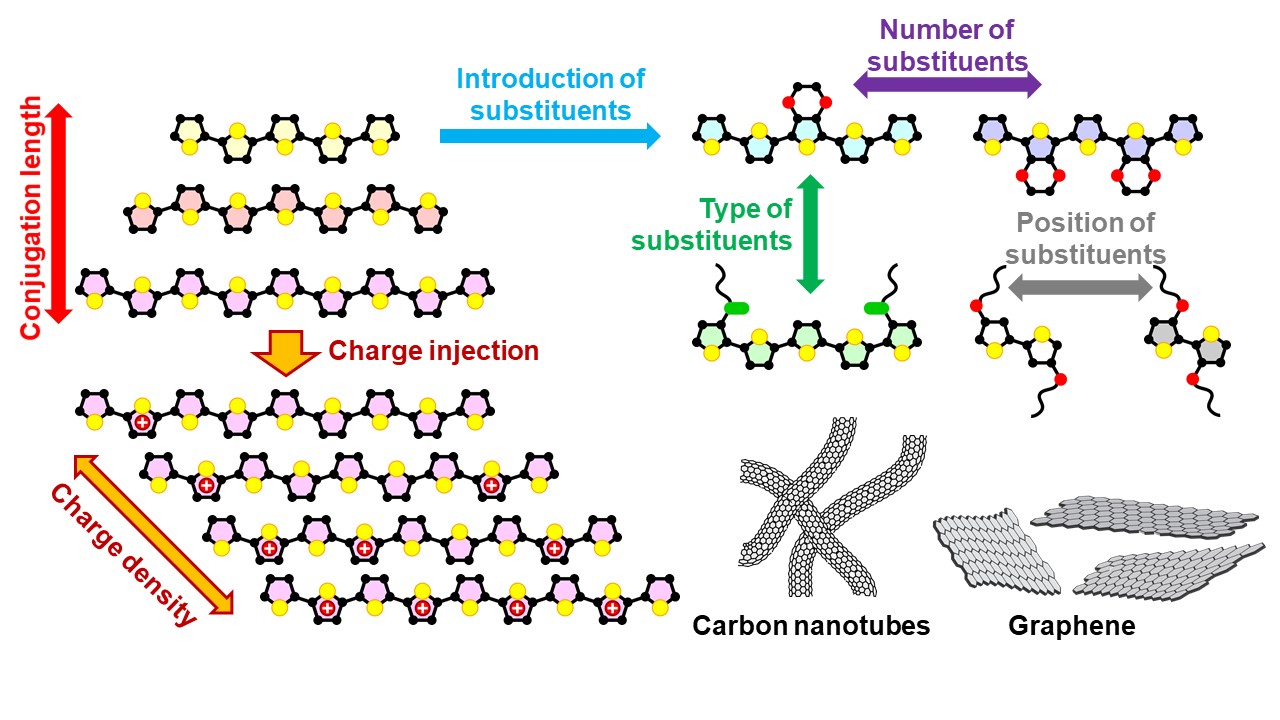

Our research group focuses on the development of high‑performance organic thermoelectric materials by precisely controlling the molecular structures of conducting polymers and the distribution of charge within their molecular frameworks. By tailoring charge density and molecular design, we aim to efficiently convert thermal energy into electrical energy.

In addition, we explore hybrid materials that combine conducting polymers with nanocarbon materials such as carbon nanotubes and graphene. Through this approach, we seek to further enhance thermoelectric performance and to establish environmentally friendly, flexible, and sustainable thermoelectric materials for next‑generation energy harvesting applications.

Our strategy for high-performance organic thermoelectrics

Watch our research introduction video

A smart window is an intelligent window whose color or transparency can change in response to external stimuli such as light or electricity. Among various mechanisms, the phenomenon in which a material changes color upon the application of an electric voltage is known as electrochromism. Smart windows based on this mechanism allow the color intensity and transparency to be controlled freely and rapidly using electrical signals. An important advantage of electrochromic smart windows is their memory effect: once the color is changed by applying electricity, the window maintains that color even after the power is turned off. This feature enables highly energy‑efficient operation.

Owing to these characteristics, electrochromic smart windows have already been commercialized in applications such as the windows of the Boeing 787 aircraft and automotive sunroofs.

(Left) A Boeing 787 photographed at Hiroshima Airport. (Right) The Boeing 787 window showing color changes of the window.

In electrochromic systems, applying an electric voltage changes the electronic state of the material. As a result, the material selectively absorbs or transmits specific wavelengths of visible light, leading to a change in its apparent color.

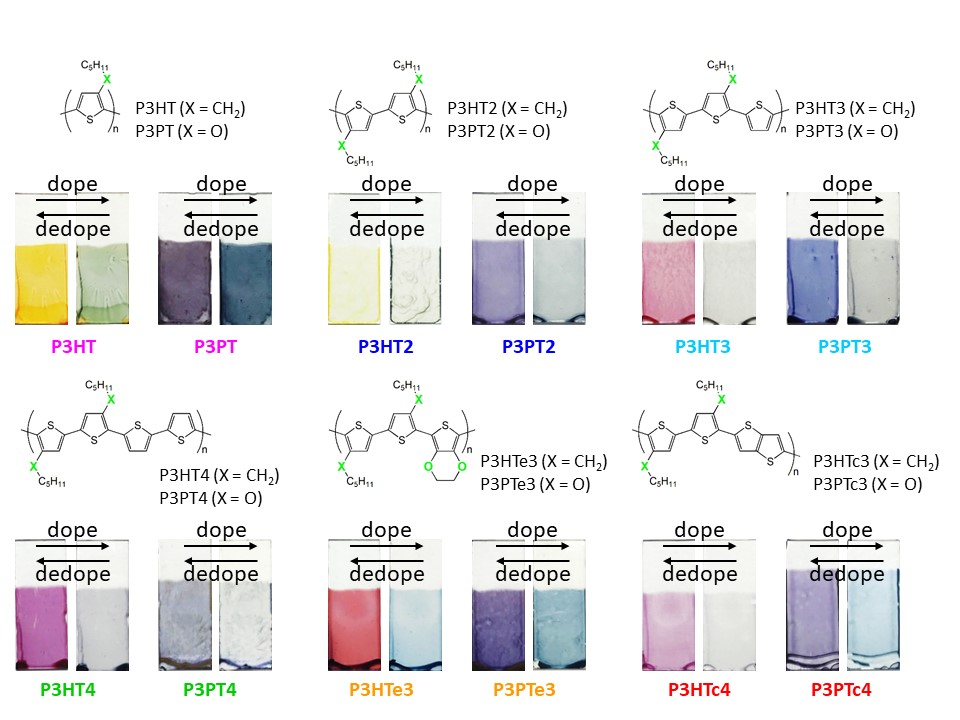

Using this mechanism, our research group is developing smart windows in which conducting polymers are coated onto electrode surfaces. By designing and tailoring the molecular structures of these polymers, we have successfully achieved a wide range of colors that can be freely controlled.

Electrochromic properties of polythiophene derivatives synthesized by our research group.

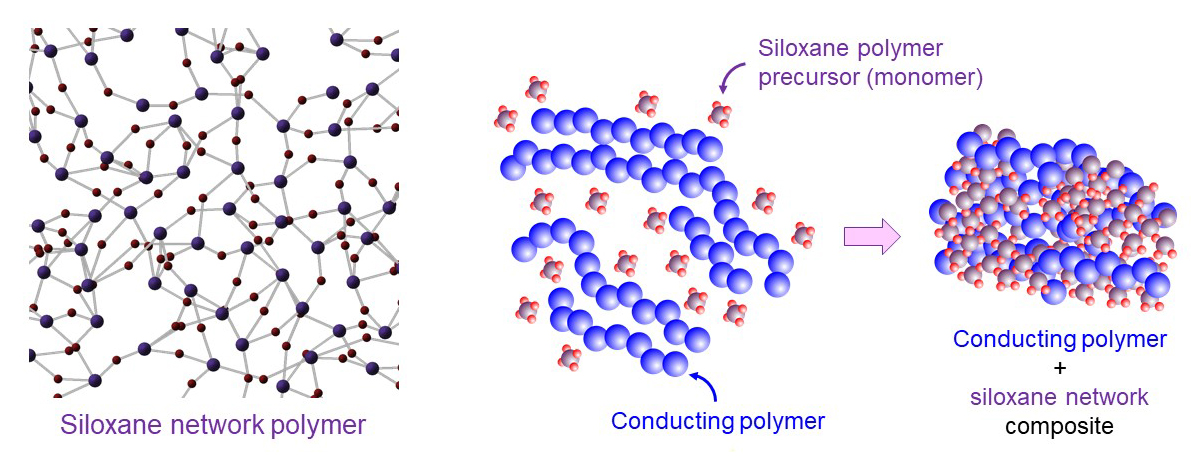

However, we encountered a critical challenge: repeated electrochemical switching over long periods can cause the polymer film to peel off from the electrode surface. To overcome this issue, we focused on siloxane‑network polymers, which possess strong chemical affinity to indium tin oxide (ITO), a commonly used electrode material. By incorporating this polymer system, we significantly improved the adhesion between the polymer film and the electrode, enabling stable and durable color switching over long operation times.

Currently, our research is expanding beyond visible color control. We are also developing new materials that can absorb infrared radiation (heat) to block intense solar heat during summer conditions. Through innovative molecular design, we aim to realize next‑generation smart windows that provide comfort and significant energy savings, contributing to a more sustainable and energy‑efficient future.

(Left) Siloxane network polymer. (Right) Composite formation of a conducting polymer with a siloxane‑based network.

Our research focuses on the utilization of carbon dioxide (CO₂), a greenhouse gas of global concern, as a resource for producing value-added materials. This work is conducted as part of an industry–academia collaboration, and details cannot be publicly disclosed due to confidentiality. We aim to contribute to the development of environmentally benign technologies toward a sustainable society.

Contamination of aquatic environments by residual pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals has become a pressing issue. For example, acetaminophen, a widely used analgesic, is excreted after use and can remain in the environment even after conventional wastewater treatment, where it is not completely degraded. PFAS (per‑ and polyfluoroalkyl substances) have been widely used in products such as water‑repellents and firefighting foams, yet they are extremely resistant to degradation and raise concerns about bioaccumulation and potential carcinogenicity. Recently, graphene oxide (GO) has attracted attention for its ability to remove various waterborne contaminants.

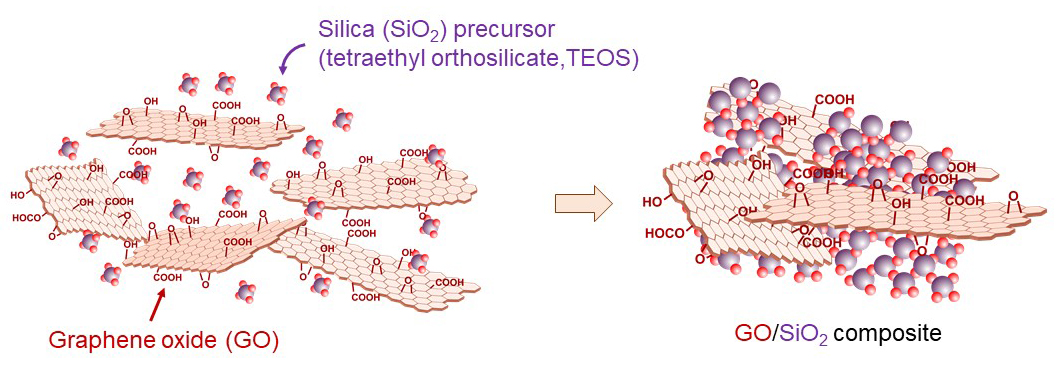

Our group has long worked with GO in the context of energy materials. In particular, we established a simple synthesis route for GO–silica (SiO2) composites by merely mixing GO with a precursors of SiO2, tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS). We demonstrated that this composite can be converted into a high‑strength transparent conductive film when only the GO component is reduced, and into a high‑capacity, durable lithium‑ion battery material when both GO and silica are reduced.

Building on these findings, we are exploring whether this readily synthesized GO–SiO2 composite can be applied to the removal of acetaminophen and PFAS from water. To this end, we are conducting international collaborative research with overseas universities to develop practical water‑purification technologies based on this material platform.

Composite formation of GO and SiO2.

(selected as a "Supplementary Journal Cover")

(selected as a "Cover Picture")

(selected as a "Front Cover")

(selected as a "Supplementary Journal Cover")

Education

Professional Experience

Award

Department of Applied Chemistry

Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering

Hiroshima University

1-4-1 Kagamiyama, Higashi-Hiroshima, Hiroshima 739-8527, Japan

Email: